While researching a recent piece about the preventable death of teenager Connor Sparrowhawk in a specialist NHS unit, I re-read a lot of old – very good and still very relevant – policy and reports.

As the piece yesterday stated, an independent report found 18-year-old Connor’s death at a Southern Health NHS Foundation Trust assessment and treatment unit was avoidable – reigniting criticism of care for people with learning disabilities.

But for more than 20 years – from 1993’s influential Mansell Report to its 2007 revised version, to the 2001 report Valuing People and the 2006 Our Health, Our Care, Our Say white paper, it’s been clear what “good looks like”.

I started this blog specifically to look at good projects, people and places, mostly related to social care. I spend some of my time finding out and writing about the good stuff that goes on – it was what I was doing before I turned to “the Connor Report“. It was a cataclysmic shift from one extreme of care to another (that brilliant, easy read version of the report is from Change Peopleby the way).

I know some brilliant folk who support people with learning disabilities and complex needs. I’ve seen first hand some of the excellent and groundbreaking support that exists for autism, learning disability and for people with challenging needs. My sister’s benefitted from the right support (albeit after a bit of a fight).

Yet despite the good practice, great intentions, campaigns, official frameworks and guidelines and reams of evidence, the pace of change for people with complex needs is slow. And poor practice remains.

When you find out about the experience of Connor’s family – his mother Sara Ryan and stepfather Richard Huggins – it is impossible not to compare it with what’s meant to happen.

Below, are just three areas I very quickly plucked from some of the papers I’ve been revisiting:

– commissioning of care services

– the concept of personalisation (tailoring care to the individual rather than a “one size fits all” approach)

– the wider issue of the status of people with learning disabilities in society (something that angers me enormously).

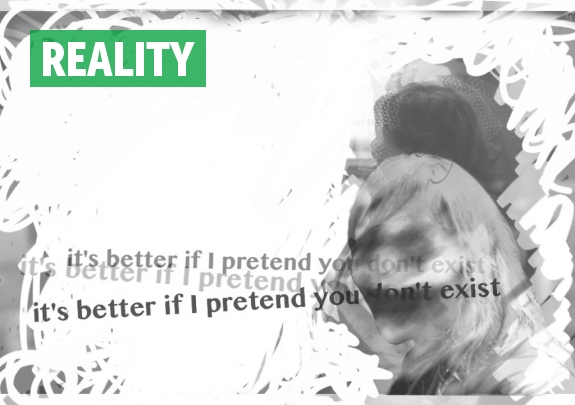

The gap between the rhetoric and the reality – most notably when it comes to people with “challenging behaviour” and complex needs – is clear. Cast your eyes over these “then” and “now” juxtaposed extracts and comments.

Then – commissioning of care services:

Mansell Report 2007 :

“Combining the different elements of services to ensure that people with learning disabilities whose behaviour presents a challenge are served well is the job of commissioning. Models of good practice have been demonstrated and service providing organisations committed to good practice exist. However, in the period since 1993 development has not kept pace with need. Placement breakdown continues to be a widespread problem in community services; people are excluded from services; assessment and treatment facilities cannot move people back to their own home; some of the placements eventually found are low value and high cost. What is it that commissioners need to do to tackle these problems? …Failure to develop local services threatens the policy of community care. Doing nothing locally is not an option. Out-of-area placements will `silt up’ and reinstitutionalisation (through emergency admissions to psychiatric hospitals or via the prisons) will occur. Special institutions and residential homes for people whose behaviour presents a challenge will be expensive but of poor quality and will attract public criticism. Overall, the efficiency of services will decrease because of the widespread lack of competence in working with people who have challenging behaviour. Commissioners will have less control over and choice of services. Individuals, carers and staff will be hurt and some individuals whose behaviour presents a challenge will be at increased risk of abuse. Staff will be at increased risk from the consequences of developing their own strategies and responses and managers will be held accountable where well-intentioned staff operate illegal, dangerous or inappropriate procedures.”

Now – commissioning of care services 2014:

Sara Ryan: “How can the commissioners not do anything [with reference to why assessment and treatment units are still commissioned]…If you commission a young person to staying in a £3,500 a week unit, then it is your duty to go and make sure that is worth it.”

Richard Huggins: “Commissioners commission public services on our behalf..Clinical commissioning group decide between competing NHS provision, so you can’t have model like that [where you buy a service and then when it goes wrong] say ‘well it’s not our fault’.”

Then – being ‘person-centred’

Valuing People, A New Strategy for Learning Disability for the 21st Century (2001) :

“A person-centred approach will be essential to deliver real change in the lives of people with learning disabilities. Person-centred planning provides a single, multi-agency mechanism for achieving this. The Government will issue new guidance on person-centred planning, and provide resources for implementation through the Learning Disability Development Fund.”

Now – being ‘person-centred’ 2014

Sara Ryan: “There is no personalisation in these units…”

Richard Huggins: “We thought they’d say ‘this is what Connor needs this is what we should do’. How that would be achieved, we had no preconception. But we thought he’d come back with a better plan, we wanted an outcome that would suit Connor.”

Then – the status of people with learning disabilities in society

Valuing People (2001) :

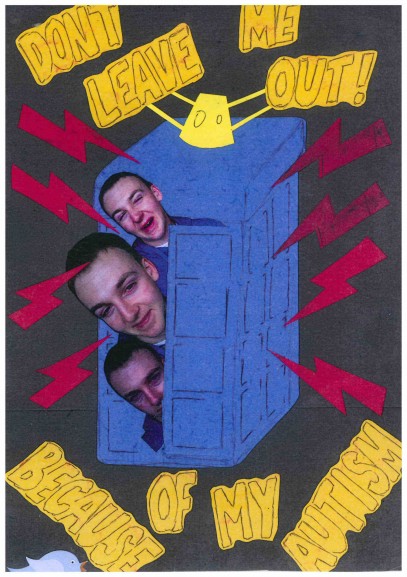

“People with learning disabilities are amongst the most vulnerable and socially excluded in our society. Very few have jobs, live in their own homes or have choice over who cares for them. This needs to change: people with learning disabilities must no longer be marginalised or excluded. Valuing People sets out how the Government will provide new opportunities for children and adults with learning disabilities and their families to live full and independent lives as part of their local communities.”

Now – the status of people with learning disabilities in society 2014

Sara Ryan: “There is a prevailing attitude about learning disability that somehow, if you’re born ‘faulty’ you cannot expect to lead a full life. What is really upsetting is fact that Connor and most young people I know are learning disabled have so much to contribute, and so much people can learn from them, but people can’t see any value in them and don’t see them as human beings, I find that really distressing.”

Richard Huggins: “There are three issues here. What happened to Connor – the care he received and how he was treated, which is still not accounted for – the way Southern Health Trust behaved as an organisation, and then there is a more general issues about the status of learning disabled people in British society.”

I could add more examples, but I think the contrast is clear.

There is a strong and growing momentum for action following Connor’s death. There is also anger but, as someone wisely told me yesterday, the anger can be channelled into action. There is also, as one chief executive of a care organisation tweeted about Connor earlier today “an onus on all of us who care to stand together alongside families seeking justice”.

* There is a “Connor Manifesto” which outlines what needs to happen next and you can find out more about the campaign on the 107 Days site and Sara Ryan’s blog.

Daniel*, 21, describes how he was supported by the charity

Daniel*, 21, describes how he was supported by the charity  Karen McCulloch, Includem project worker, on how she supported Daniel:

Karen McCulloch, Includem project worker, on how she supported Daniel: