Scrounger or superhero – and little in between. This is how people like my sister, who happens to have a learning disability, are generally seen in society and the media.

The missing part of the equation is what led me to develop the book Made Possible, a crowdfunded collection of essays on success by high-achieving people with learning disabilities. I’m currently working on the anthology with the publisher Unbound and it’s available for pre-order here.

I’ve just spoken about the role of media in shaping attitudes to disability, and how and why is this changing at an event – Leaving No One Behind at Birmingham City University. The day was organised by the charity Include Me Too and community platform World Health Innovation Summit.

I wanted to support the event because of its aim to bring together a diverse range of people, including campaigners, families, self-advocates and professionals (check out #LeavingNoOneBehind #WHIS to get a feel for the debate).

This post is based on the discussions at the event, and on my views as the sibling of someone with a learning disability and as a social affairs journalist. I’ve focused on print and online media influences perceptions; broadcast media clearly has a major role – but it’s not where my experience over the past 20 years lies.

Firstly, here’s Raana:

Raana’s 28. She loves Chinese food. She adores listening to music (current favourite activity: exploring Queen’s back catalogue – loud). She’s a talented baker and has just started a woodwork course. She has a wicked, dry sense of humour (proof here).

She also also has the moderate learning disability fragile x syndrome. She lives in supported housing and will need lifelong care and support.

The way I describe Raana – with her character, abilities first, diagnosis, label and support needs second, is how I see her. It’s how her family, friends and support staff see her.

But it’s not how she would be portrayed in the mainstream press.

Instead, this comment from the writer and activist Paul Hunt, reflects how she and other learning disabled people are seen:

“We are tired of being statistics, cases, wonderfully courageous examples to the world, pitiable objects to stimulate funding”. Paul Hunt wrote these words in 1966 – his comment is 51 years old, but it’s still relevant (charity fundraising has changed since then, but the rest of the words are spot on – sadly).

Say the words “learning disability” to most people and they will think of headlines about care scandals or welfare cuts.

These reinforce stereotypes of learning disabled as individuals to be pitied or patronised. The middle ground is absent; the gap between Raana’s reality and how she’s represented is huge.

How often, for example, do you read an article about learning disability in the mainstream media which includes a direct quote from someone with a learning disability?

Stories are about people, not with people.

Caveat: as a former national newspaper reporter, I know only too well that the fast-pace of the newsroom and the pressure of deadlines mean it’s not always possible to get all the interviews you’d like. This is harder for general news reporters reacting to breaking stories than it is for specialists or feature writers who have just the right contacts and/or the time to reflect every angle of the story. But there’s still more than can be done – and much of it is very simple.

Take the language used in news and features.

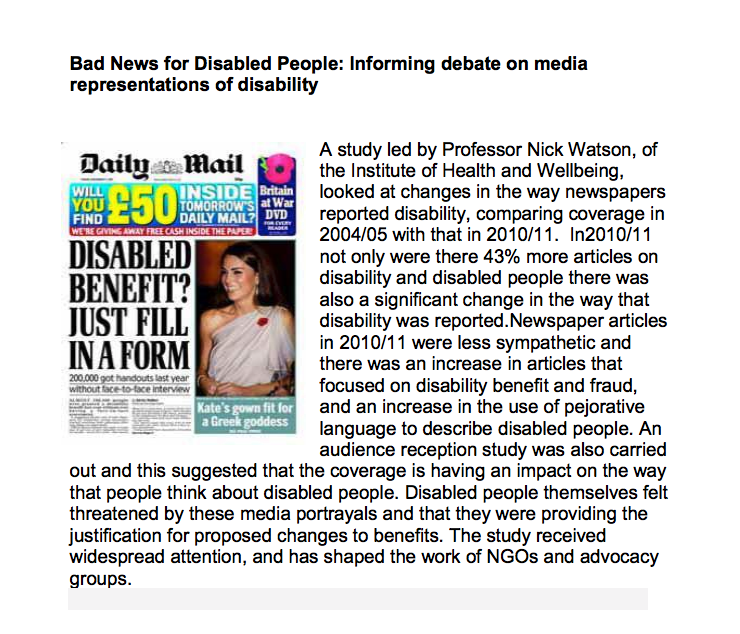

There’s a huge amount of research shows how media influences public attitudes. One focus group project by Glasgow University a few years ago showed people thought up to 70% of disability benefit claims were fraudulent. People said they came to this conclusion based on articles about ‘scroungers’.

The real figure of fraudulent benefit claims? Just 1 per cent.

The language used in mainstream media is often problematic. I wince when I read about people “suffering from autism” – “coping with a learning disability” – or being “vulnerable”.

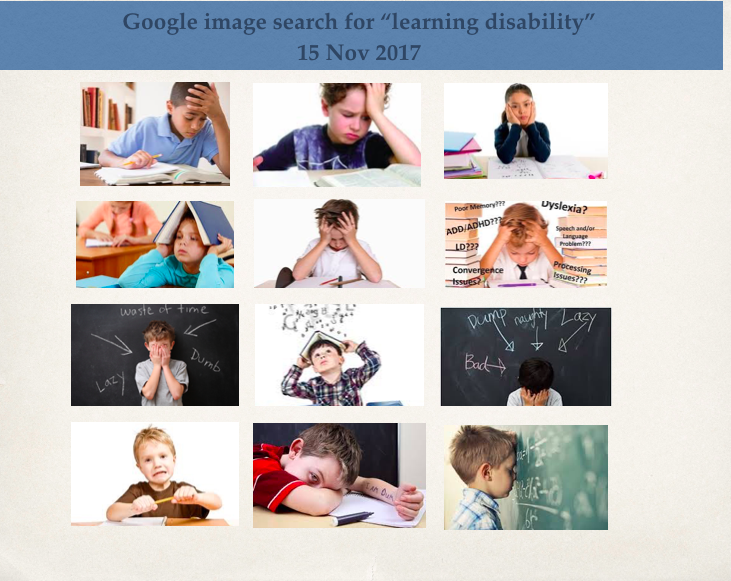

Images used in stories often don’t help.

As a quick – but very unscientific – litmus test – I typed the words “learning disability” into Google’s image search.

This is a flavor of what I found – the most common pictures that came up were the dreadful “headclutcher” stock image that often accompanies articles about learning disability.

These images say, defeat, frustration, confusion, negativity.

This is not how I see my sister, her friends or the learning disabled campaigners I know.

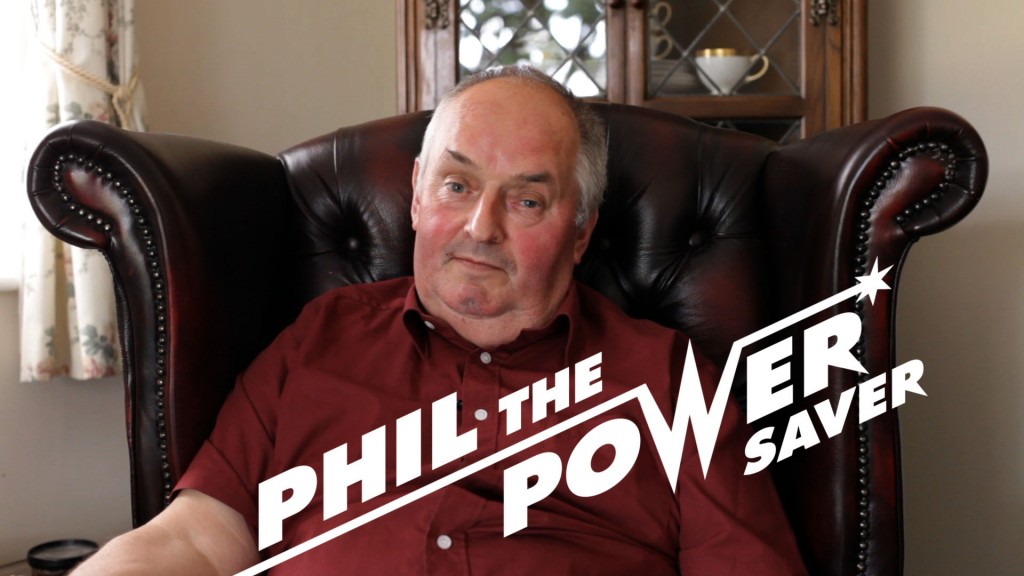

This is more how I see them:

This shot is from a story I did a few days ago about Martin, Martin’s 22 and works part-time as a DJ at a local radio station (you can read about him here). Martin also happens to have a moderate learning disability and cerebral palsy.

We need more of this.

An obvious – but nonetheless important – point to make here is about the disability and employment gap. A more diverse workforce in the creative sector will impact on representation. Only 6% of people with learning disabilities work, for example, but around 65% want to (I wrote about this issue in the Guardian recently)

But there is cause for optimism. There is a slow but significant shift in the representation of learning disabled people thanks to the rise in grassroots activism, family campaigning, self-advocacy and the growing empowerment agenda.

Social media is helping spread awareness and spread a different narrative.

This rise in self-advocacy is what led me to develop Made Possible. The book’s aim is to challenge stereotypes; it targets a mainstream readership and introduces readers to learning disabled people in areas like arts, politics and campaigning. Their achievements are impressive regardless of their disability.

While I’m researching the book, I’m trying to keep three words in mind – attitude, ability, aspiration:

Am I sharing experiences that help shift public attitudes?

Am I reporting people’s abilities, not just their disabilities?

Am I reflecting people’s potential – what do they aspire to achieve, and how can this happen?

And although I’m focusing on positive representation of learning disability, it’s worth stressing that there’s an equally vital need to highlight the challenges.

Challenges like the impact of austerity, for example, or the health inequalities, or the fact that over 3,000 people are still locked away in inappropriate institutional care.

The two go hand – a more authentic portrayal of people’s lives (their qualities, hopes and aspirations) and reporting the inequalities they face.

Because readers are more likely to care about the inequality and support the need to solve it if they feel closer to the real people experiencing that inequality – if they stop seeing learning disabled people as “the other”, or as statistics (as Paul Hunt wrote over 50 years ago..) and as people first.

It’s often said that media should reflect, serve and strengthen society. Which means we have to be more accurate and authentic about how we include and portray a huge section of that society – including my sister – which happens to have a disability.