It is now three years since the abuse inflicted on people with learning disabilities at Winterbourne View highlighted the desperate need to get people out of such institutional settings.

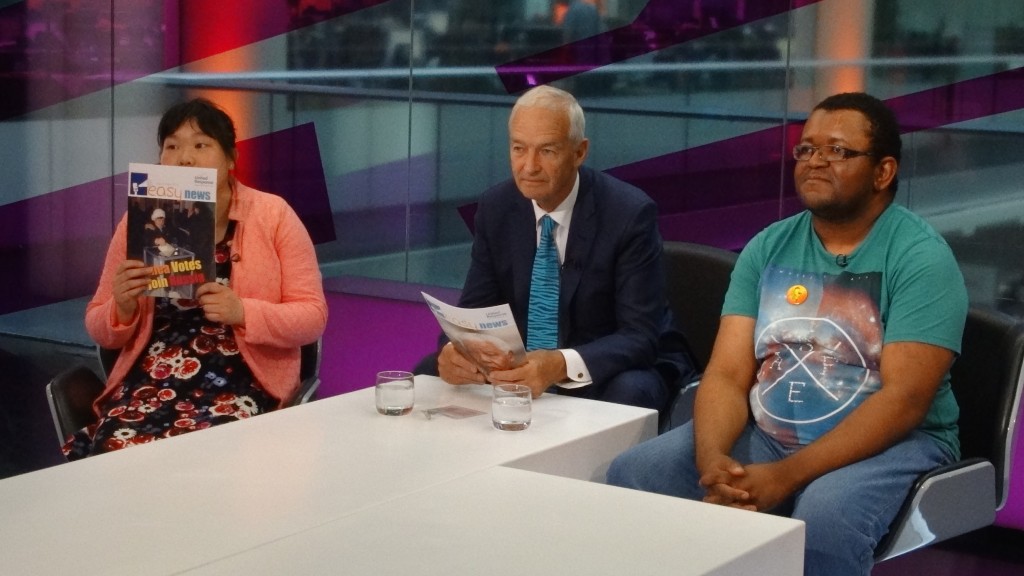

In those three years, we know of two people who have died in these kind of assessment and treatment units since then (Connor Sparrowhawk, pictured at the top of the page, and Stephanie Bincliffe). Many more – Tianze and Stephen (also pictured above) among them – are still being placed by health and social care authorities in such places.

The “abject failure” to move people out of these woeful environments is clear. The piece in today’s Guardian looks at this issue, including a report today by Sir Stephen Bubb, Winterbourne View – Time to Change and the momentum for change driven by families and campaigners.

Assessment and treatment centres are inappropriate institutions, modern day versions of the prison-like settings we thought we’d dismantled years ago – holding pens in which to warehouse some of society’s most vulnerable people.

Read that first sentence again – two people died (they had no life-threatening illnesses) in a clinical environment where they were placed for care, assessment and treatment – and ask how it is possible that we can let this happen?

Why “we”? Because of the collective responsibility: public and private sector funders enable these places to be created; health and social care providers run them; commissioners place people in them; politicians and policy makers seem unable to hold anyone to account for them; there is little mainstream interest media reporting in this area and the public – beyond shock at the odd high profile headline – is generally apathetic.

The fact that there have been two deaths in the three years since we’re meant to have eradicated these kinds of places is starkly made by Sara Ryan in today’s Guardian. She describes such units as “waste bins of life”.

Sara’s son Connor Sparrowhawk (aka Laughing Boy or LB) died a preventable death last year in a Southern Health NHS unit, and the widespread outrage that followed created the Justice for LB campaign with the related 107 Days drive, and draft disability rights legislation in LB’s name, the LB Bill.

It’s hoped that a green paper in February next year will reflect some elements of the bill.

Disability and human rights barrister Steve Broach, who is helping to draft the bill alongside Connor’s parents (Sara Ryan and Richard Huggins), Mark Neary and George Julian, says the project is using social media to galvanise a diverse community, including people with disabilities, professionals, families and academics. “We’re trying to crowdsource changes to the law – people are patronised and it’s wrongly assumed that disabled people and their families cannot understand their legal rights,” says Broach.

Kevin Healey, campaigner for autism rights who has supported three of the families mentioned in the piece today, says that people are effectively “penalised for having a learning disability or autism”. He says the successful campaigns to return people home are vital, but rare.

Healey adds: “It’s like we’re going back to the days of the 1940s when people with autism used to be institutionalised, but this is the 21st century.” Healey warns that where the authorities return people home, it is important to protect and preserve any new community-based packages of care amid the sweeping welfare cuts.

One mother, Leo Andrade-Martinez, told me of the son she is campaigning for (Stephen has been moved 80 miles away from home and restricted to a two-hour weekly visit from his parents) that “no one should suffer like this”.

Her words are horribly familiar to anyone interested in disability rights.

For more than 20 years – from 1993’s Mansell Report to the 2006 Our Health, Our Care, Our Say white paper, it’s been clear what “good looks like” when it comes to supporting people with learning disabilities. But still, seeing it in practice is the exception and not the rule.

You can read the full piece in The Guardian here.

Links for further reading:

* Petitions for Tianze Ni and Stephen Andrade-Martinez, both in units miles from their families. Website for campaigner Kevin Healey involved in the family campaigns.

* New Justice for LB website from where you can access different parts of the campaign and the latest updates, including news on the private members bill for disability rights

* The story of how the LB Bill is being shaped through crowdsourcing