For regular updates, find me on Twitter and Instagram or LinkedIn and find my latest articles on my website.

Category Archives: Blogging

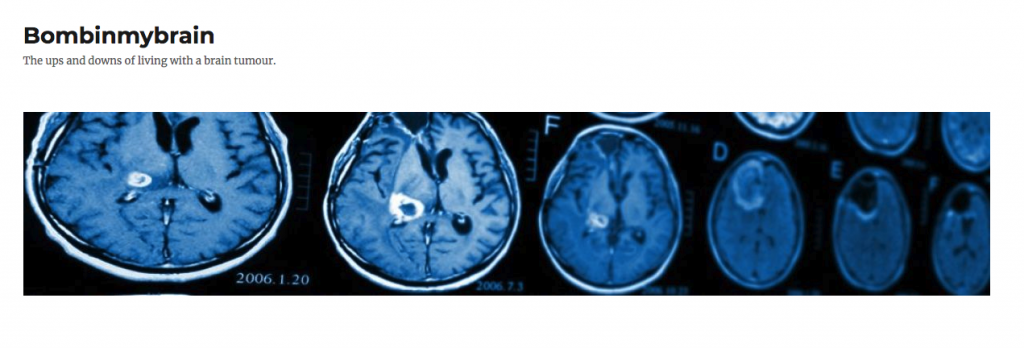

Bomb in my brain: new blog on living with a brain tumour

What’s it like living with a brain tumour?

My friend Jude Bissett can tell you – she first got the news in 2003 and has just launched a new blog about life with a brain tumour, Bomb in my brain. The site is pretty new, but it’s easy to see how Jude’s powerful and honest testimony of a life changing experience will be an important resource for others undergoing the same thing. And even if the issue isn’t something you’ve experience of, it’s an engaging and insightful read.

Jude explains: “I evaded writing about what happened for 15 years. Why? I don’t really know. It was in my head for all that time, usually safely in the background, largely ignored but with occasional flashbacks and incidents that forced it forward. And this time it’s back in a way I can’t ignore and the time feels right to document it, in part therapy, in part to have an accurate record and in part to help anyone else who may face a similar situation and be seeking clues as to what they might expect. Though it will only be clues, we are all different, we all experience life differently.”

Here’s a recent extract from September:

By the end of my “break” I am feeling basically back to normal. The summer holidays have been particularly long with glorious weather, it felt like they would go on for ever. Then before I know it, Posy has her birthday and I am due back at hospital for round two. No tears for me this time, not now I know the drill. I fair skip into the Colney Centre, ready for my spot in a comfy chair and a nice cup of tea from a McMillan volunteer. During the week I had a blood test done at my local surgery. As ever they found it difficult to squeeze much out of me but there was enough apparently for them to check my platelets which were excellent, thank you smoothies! They need to check the white count but they have a machine on site to do this.

My Portacath is used to get the blood and I am delighted it can be used both to get blood out as well as do the infusion, what a clever device, how smug I feel for getting it put in!After a few minutes the nurse returns. She is very sorry but they can’t proceed with my treatment. This news comes as an absolute shock to me, this is not something I thought would happen. It seems my white count is too low. It has to be over 1 and mine is languishing at 0.24. But I feel fine! What has gone wrong? What have I been doing wrong? I’ve had all the smoothies with spinach and seeds and other shite, why hasn’t that been good enough? “it’s just the treatment” the nurse keeps repeating. I don’t understand and I feel unaccountably upset. The nurse tells me they’ll defer me a week and my count will come back up. I should be pleased at the reprieve but I am fretful as I’ve plans to attend a good friend’s 50th at the end of the summer and I’m worried this will throw out my timing. But I calculate the next week will still be ok and I defer for the week and return home.

You can read more of this extract at Bomb in my brain by Jude Bissett and please share widely.

The Social Issue – on a summer break

As the Twitter screenshot above says, I’m on a break from blogging and tweeting so I can progress the book, Made Possible, a collection of essays on success by high achieving people with learning disabilities (yes, you read that right – this book’s all about shattering stereotypes!).

You can find out more about this crowdfunded collection of essays here which is being published thanks to some incredible support from its patrons (a list of supporters so far is available on this page if you scroll down to ‘supporters’).

Success – as written by people with learning disabilities

People with learning disabilities are pitied or patronised, but rarely heard from in their own words.

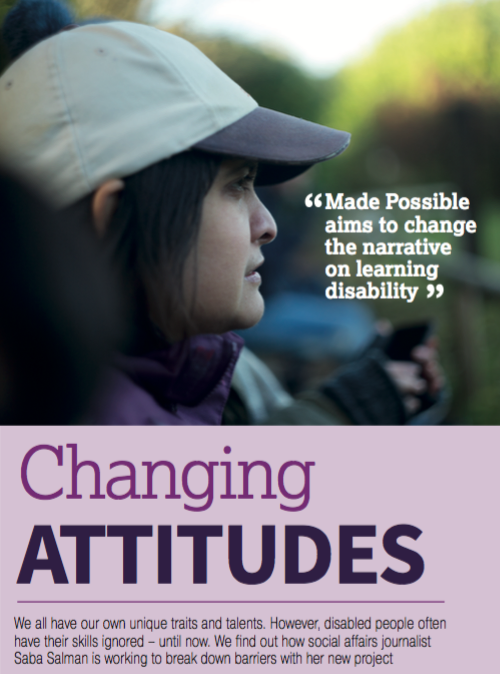

Made Possible is an attempt to challenge this and change attitudes – it’s the crowdfunded book I’m editing, featuring essays on success by high achieving people with learning disabilities.

It was very cool to see Made Possible sweep into 2018 with a feature in the January issue of disability lifestyle magazine Enable. In the print edition, Enable used this shot of my baseball-cap loving sister (who has partly inspired the book) looking thoughtful and determined:

The article describes the book’s aim of putting learning disabled people’s personalities and potential before their disability. The editorial also reflects Made Possible’s diverse range of essay contributors, and explains its goal of challenging stereotypes: “Many traditional texts focusing on disability, be it physical, sensory or learning, are factual in a medical or academic context. Made Possible is set to change this narrative by appealing to a wider audience in a bid to open the world of creativity, talent, varied skills and experiences to the general public.”

The book’s contributors have also been busy developing and working on the essays, and we’ve been unpicking the concept of success in the process. As the Enable article says of Made Possible’s theme, “success is different for everyone”, and although we’re at the inital stages, it’s already fascinating (and often surprising) to discover the essayists’ views on achievement – and who defines this.

At a time when disabled people bear the brunt of society’s inequalities, from healthcare to housing and employment, redressing the imbalance and describing how people can fulfil their ambitions is more vital than ever (you can read more about the timely aspects of this book in this recent Guardian piece by scrolling down to “Why do we need this book?”).

It’s also been superb to see new supporters pre-ordering copies of the book – thank you! If you’ve recently joined us, do connect if you’d like to on Twitter, LinkedIn, Facebook or Instagram using the hashtag #MadePossible.

Also much gratitude to those of you already in touch and mentioning the book on social media, it’s a tip top way to keep #MadePossible on the radar. Do continue to share the Made Possible page with others you think might be interested in what we’re trying to do.

To find out more, check out Made Possible on the website of its publisher, Unbound or see this page elsewhere on the blog.

Scrounger or superhero, and little in between: learning disability in the media

Scrounger or superhero – and little in between. This is how people like my sister, who happens to have a learning disability, are generally seen in society and the media.

The missing part of the equation is what led me to develop the book Made Possible, a crowdfunded collection of essays on success by high-achieving people with learning disabilities. I’m currently working on the anthology with the publisher Unbound and it’s available for pre-order here.

I’ve just spoken about the role of media in shaping attitudes to disability, and how and why is this changing at an event – Leaving No One Behind at Birmingham City University. The day was organised by the charity Include Me Too and community platform World Health Innovation Summit.

I wanted to support the event because of its aim to bring together a diverse range of people, including campaigners, families, self-advocates and professionals (check out #LeavingNoOneBehind #WHIS to get a feel for the debate).

This post is based on the discussions at the event, and on my views as the sibling of someone with a learning disability and as a social affairs journalist. I’ve focused on print and online media influences perceptions; broadcast media clearly has a major role – but it’s not where my experience over the past 20 years lies.

Firstly, here’s Raana:

Raana’s 28. She loves Chinese food. She adores listening to music (current favourite activity: exploring Queen’s back catalogue – loud). She’s a talented baker and has just started a woodwork course. She has a wicked, dry sense of humour (proof here).

She also also has the moderate learning disability fragile x syndrome. She lives in supported housing and will need lifelong care and support.

The way I describe Raana – with her character, abilities first, diagnosis, label and support needs second, is how I see her. It’s how her family, friends and support staff see her.

But it’s not how she would be portrayed in the mainstream press.

Instead, this comment from the writer and activist Paul Hunt, reflects how she and other learning disabled people are seen:

“We are tired of being statistics, cases, wonderfully courageous examples to the world, pitiable objects to stimulate funding”. Paul Hunt wrote these words in 1966 – his comment is 51 years old, but it’s still relevant (charity fundraising has changed since then, but the rest of the words are spot on – sadly).

Say the words “learning disability” to most people and they will think of headlines about care scandals or welfare cuts.

These reinforce stereotypes of learning disabled as individuals to be pitied or patronised. The middle ground is absent; the gap between Raana’s reality and how she’s represented is huge.

How often, for example, do you read an article about learning disability in the mainstream media which includes a direct quote from someone with a learning disability?

Stories are about people, not with people.

Caveat: as a former national newspaper reporter, I know only too well that the fast-pace of the newsroom and the pressure of deadlines mean it’s not always possible to get all the interviews you’d like. This is harder for general news reporters reacting to breaking stories than it is for specialists or feature writers who have just the right contacts and/or the time to reflect every angle of the story. But there’s still more than can be done – and much of it is very simple.

Take the language used in news and features.

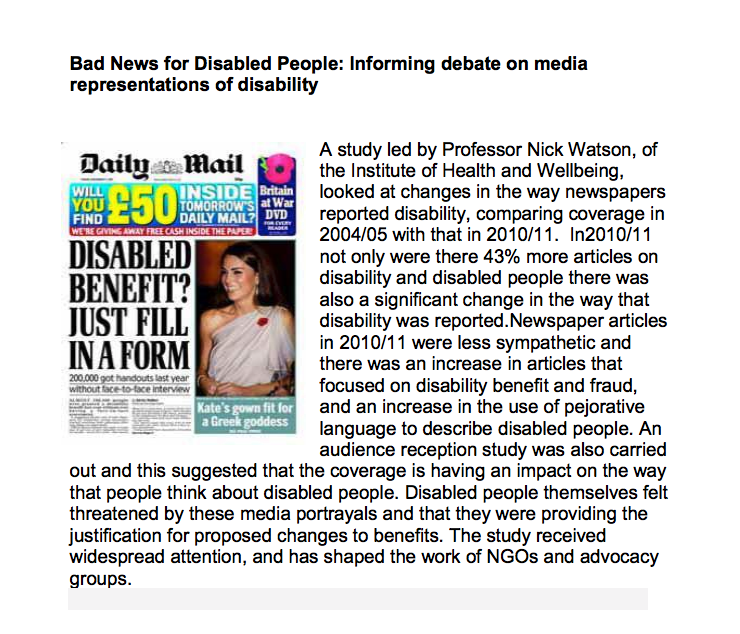

There’s a huge amount of research shows how media influences public attitudes. One focus group project by Glasgow University a few years ago showed people thought up to 70% of disability benefit claims were fraudulent. People said they came to this conclusion based on articles about ‘scroungers’.

The real figure of fraudulent benefit claims? Just 1 per cent.

The language used in mainstream media is often problematic. I wince when I read about people “suffering from autism” – “coping with a learning disability” – or being “vulnerable”.

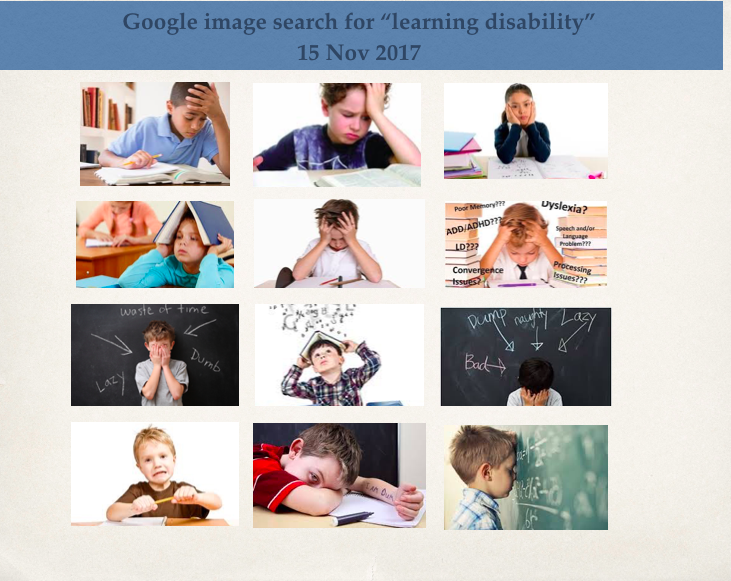

Images used in stories often don’t help.

As a quick – but very unscientific – litmus test – I typed the words “learning disability” into Google’s image search.

This is a flavor of what I found – the most common pictures that came up were the dreadful “headclutcher” stock image that often accompanies articles about learning disability.

These images say, defeat, frustration, confusion, negativity.

This is not how I see my sister, her friends or the learning disabled campaigners I know.

This is more how I see them:

This shot is from a story I did a few days ago about Martin, Martin’s 22 and works part-time as a DJ at a local radio station (you can read about him here). Martin also happens to have a moderate learning disability and cerebral palsy.

We need more of this.

An obvious – but nonetheless important – point to make here is about the disability and employment gap. A more diverse workforce in the creative sector will impact on representation. Only 6% of people with learning disabilities work, for example, but around 65% want to (I wrote about this issue in the Guardian recently)

But there is cause for optimism. There is a slow but significant shift in the representation of learning disabled people thanks to the rise in grassroots activism, family campaigning, self-advocacy and the growing empowerment agenda.

Social media is helping spread awareness and spread a different narrative.

This rise in self-advocacy is what led me to develop Made Possible. The book’s aim is to challenge stereotypes; it targets a mainstream readership and introduces readers to learning disabled people in areas like arts, politics and campaigning. Their achievements are impressive regardless of their disability.

While I’m researching the book, I’m trying to keep three words in mind – attitude, ability, aspiration:

Am I sharing experiences that help shift public attitudes?

Am I reporting people’s abilities, not just their disabilities?

Am I reflecting people’s potential – what do they aspire to achieve, and how can this happen?

And although I’m focusing on positive representation of learning disability, it’s worth stressing that there’s an equally vital need to highlight the challenges.

Challenges like the impact of austerity, for example, or the health inequalities, or the fact that over 3,000 people are still locked away in inappropriate institutional care.

The two go hand – a more authentic portrayal of people’s lives (their qualities, hopes and aspirations) and reporting the inequalities they face.

Because readers are more likely to care about the inequality and support the need to solve it if they feel closer to the real people experiencing that inequality – if they stop seeing learning disabled people as “the other”, or as statistics (as Paul Hunt wrote over 50 years ago..) and as people first.

It’s often said that media should reflect, serve and strengthen society. Which means we have to be more accurate and authentic about how we include and portray a huge section of that society – including my sister – which happens to have a disability.

The Social Issue’s on a summer break

As you may have spotted, I’m on a blogging break for July and August, but will be tweeting (@Saba_Salman) when I can and will definitely be back to full speed in early September.

Thanks v much to everyone who’s been following the blog, sharing the posts and suggesting topics and projects to cover.

Indignation and initiative vs institutional inertia

This is a post that originally appeared on the #107days of action campaign site, raising awareness about the death of Connor Sparrowhawk who died a preventable death in specialist NHS unit last year:

Imagine if you had £3,500 a week to run a campaign, consider the awareness you could raise with even a tenth of that.

Now multiply £3,500 – the average weekly cost of a place at an assessment and treatment unit (ATU) – by 3,250 – the number of learning disabled people in such units. That’s an indicator of the costs involved in using controversial Winterbourne View-style settings.

Just over a year ago, 18-year-old Connor Sparrowhawk, aka Laughing Boy or LB, was admitted to a Southern Health NHS Trust ATU where he died an avoidable death 107 days later.

In contrast to the vast amounts spent by commissioners on places like the one where LB died, the #JusticeforLB campaign sparked by his death is ‘funded’ solely by goodwill. No PR team crafting on-message missives, no policy wonks collating information, no consultants advising on publicity.

#107days of action began on Wednesday 19 March, a year to the day Connor went into Slade House, and continues until the first anniversary of his death, Friday 4 July 2014. Half the aim – and I’ll come to the other half at the end of this post – is to “inspire, collate and share positive actions being taken to support #JusticeforLB and all young dudes”. The goal is to capture the “energy, support and outrage” ignited by LB’s death.This post, around halfway through #107days and written from the perspective of having reported on #JusticeforLB at the start of the campaign, looks at what’s been achieved so far.

I’m not describing the “abject failure” of progress to rid social care of Winterbourne-style settings – care minister Norman Lamb’s words – the sort of apologies for care where compassion is often as absent as any actual assessment or treatment. Nor do I write about the errors at Southern (you can read here about the enforcement action from health regulators after a string of failures). I want to explain, from my interested observer’s standpoint, the impact of #107days and what might set it apart from other awareness drives.

It’s a timely moment to do this. It is now three years since Winterbourne, less than a week after Panorama yet again highlighted abuse and neglect in care homes and a few days since new information on the use of restraint and medication for people in units like LB’s. The campaign reflects not only the importance of #JusticeforLB, but also an unmet need to finally change attitudes towards vulnerable people (and it’s not as if we don’t know what “good care” looks like).

There is a palpable sense that the #107days campaign is different. Talking to journalists, families, activists, academics, bloggers and social care providers, the word “campaign” doesn’t adequately define #107days. It’s an, organic, evolving movement for change, a collaborative wave of effort involving a remarkably diverse range of folk including families, carers, people with learning disabilities, advocates, academics and learning disability nurses.

It’s worth noting the campaign’s global reach. LB’s bus postcard has been pictured all over the UK and as far away as Canada, America, Ireland, France, Majorca and São Paulo. LB has touched a bus driver in Vancouver and brownies in New Zealand.

Because of the blog run by Connor’s mother Sara Ryan (launched long before his death), LB and his family are not mere statistics in a report or anonymised case study “victims” in yet another care scandal. Instead we have Connor: a son, brother, nephew, friend, schoolmate, neighbour – and much more – deprived of his potential. We forget neither his face and personality nor the honest grief of a family facing “a black hole of unspeakable and immeasurable and incomprehensible pain”.

Yet while anger and angst has sparked and continues to fan #107days, the overwhelming atmosphere is optimistic. There is the sense that outrage, can should and will force action (and it’s worth mentioning, as #JusticeforLB supporters have stressed, exposing bad care begs a focus on good care – lest we forget and tar all professional carers with the same apathetic brush).

Both in its irreverent attitude and wide-ranging activity, this is no orthodox campaign. It is human and accessible because of its eclectic and inclusive nature (see, for example, Change People’s easy read version of the report into Connor’s death). And at the heart of the campaign lie concrete demands. In its bottom-up, social media-driven, grassroots approach and dogged determination, #107days has a hint of the Spartacus campaign against welfare cuts (Spartacus activist Bendy Girl is supporting #JusticeforLB through her work with the newly formed People First England).

As for impact so far, daily blogposts have attracted over 25,000 hits with visitors from 63 countries. There have been 7,000 or so tweets (which pre-date #107days) 1,380 followers, the #justiceforLB hashtag has been used more than 3,560 times and the #107days hashtag more than 2,000 times in the last month (thanks to George Julian for the number crunching). So far, the total amount raised for Connor’s family’s legal bills is around £10,000.

I can’t list each #107day but suffice it to say that the exhaustive activities and analysis so far include creative and sporting achievements highlighting the campaign as well as education-based events (or as Sara described progress on only Day 6 of #107: “Tiny, big, colourful, grey, staid, chunky, smooth, uncomfortable, funny, powerful, mundane, everyday, extraordinary, awkward, shocking, fun, definitely not fun, political, politically incorrect, simple, random, harrowing, personal, in your face, committed, joyful, loud, almost forgettable, colourful and whatever events”).

Along with blogs, beach art and buses in Connor’s name, there’s an LB truck, the tale of two villages’ awareness-raising, a hair-raising homage, autobiographical posts about autism, siblings’ stories, sporting activities, and lectures. And patchwork, postcards, pencil cases, paddling (by a 15-year-old rower) and petition-style letters (open to signatures).

It’s worth noting that while learning disability should be but isn’t a mainstream media issue, there have been pieces in the Guardian and Daily Telegraph plus important coverage on Radio 4 , BBC Oxford and in the specialist press. BBC Radio Oxford‘s Phil Gayle and team have followed developments relentlessly and Sting Radio produced an uplifting show on the first day of the campaign. While some of this coverage pre-dates #107days, it reflects how media attention has been captured solely thanks to the efforts of Connor’s family and supporters (links to other coverage are on Sara’s blog).

As for reaching the key figures who could help make the changes #107days wants, the campaign has had contact with health secretary Jeremy Hunt, care minister Norman Lamb, chief inspector of adult social care Andrea Sutcliffe and Winterbourne improvement programme director Bill Mumford, care provider organisations and staff.

Earlier, I described the first half of #107days’ aims to “inspire, collate and share positive actions” and capture the “energy, support and outrage” ignited by LB’s death. Based on the efforts and impact so far, and the campaign is clearly on track.

But the remaining target – to “ensure that lasting changes and improvements are made” – is more elusive, largely because it lies outside the responsibility and remit of members of the #107days campaign.

Contrast the collective nerve, verve, indignation and initiative of the last 46 days to what Norman Lamb calls the historic “institutional inertia” of NHS and local government commissioners, a cultural apathy undermining plans to move more people out of Winterbourne-style units.

The existence and continued use of ATUs might be a challenging and seemingly intractable problem. But that’s not good enough a reason for commissioners – and those who run and govern such places – to ignore the problem. There are good intentions coming from some in authority; people just need to put their collective muscles where their mouths are. Doing that sometime during the remaining 60 days of the campaign for Connor seems like the right thing to do.

He should never have died

I launched this blog as a platform for some of the excellent, uplifting, often unsung, good practice in social and public policy.

In contrast, this week I’ve been finding out about some of the worst care possible.

The opposite of “care”, in fact.

A host of very adept, passionate bloggers and campaigners have been demanding not only answers, but action after the death last year of Connor Sparrowhawk. Connor, 18, died while “being cared for” at a Southern Health Trust in-patient unit in Oxfordshire for people with learning disabilities.

As Connor’s mother Sara has said, “He should never have died and the appalling inadequacy of the care he received should not be possible in the NHS.” Sara’s powerful blog includes links to bloggers and commentators whose words are well worth reading.

I had to share Sara’s beautiful and powerful slideshow here; please watch it if you’ve not seen it before. And if you have already seen it, watch it again to remind yourself of the very real people and families behind the astonishing inequalities in care experienced by people with learning disabilities.

Much has been written about Connor, and more will be – although clearly we need more action than words alone – but taken together, Sara’s slideshow and these stark words from the independent report published last week tell you much of what you need to know: “the death of [Connor] was preventable”.

* Follow #JusticeforLB on Twitter @JusticeforLB

* Read more on Sara’s blog and sign up for email updates here

The Social Issue, part of the Guardian’s blogging network

Good to see a nod to the blog on the Guardian Select pages this morning, especially when the page featured is from the Bound exhibition about disability issues. A reminder of the point of this site: “It champions the good stuff going on in terms of support, much of it small unsung hero-type projects, which is important at a time that so many charities and support schemes are losing funding.” Read more here.

Writing about wrongs: can social affairs journalism make a difference?

So, I’m commissioned by a children’s charity to interview a single mum it’s been working with. She’s got five kids; black mould spreads thickly across her kitchen ceiling and down the back wall. One of her daughters, a little girl with asthma, sleeps in a pink bedroom so icily cold I feel my skin shrink when we look in. A single photograph of a baby lost to cot death is unobtrusively placed among the many pictures of her other children displayed in the front room.

There’s a housing association building site at the end of the terraced row, but this woman can’t get hold of the £400 she needs to secure one of the warm, dry family houses that will soon be available.

I write my piece feeling angry and hopeless. My fee is more than the money she needs for that deposit. I wrestle with the thought that I should give it to her. I don’t.

A year on, I still wonder if I should have done. This is hardly war reporting, but these are people living on a front line. They’re who I write about. And then I disappear off, my notebook full, my deadline pressing. I rarely see them again.

Does this kind of journalism change anything? I don’t know. It’s what I do, what I can do, what I have time to do. I know it’s not enough.

Though what’s playing out in the Leveson enquiry means that rotten practices are being dragged through the mire, the level of underlying suspicion about journalism saddens me, because it’s based on a misunderstanding of what any kind of serious journalism is about.

I don’t do this job because I want to stiff as many people as possible in the name of selling papers. I do it because stuff goes badly wrong in certain bits of public life, and in the small way that writing articles allows, I want to ask why – then persuade, cajole, flatter or embarrass people into giving me the answer.

The judgements I make in writing a piece may be taken fast, but they aren’t taken lightly. For instance…

I’m constantly examining the ethics of how I go about writing a piece. Particularly if an interviewee is vulnerable or not media savvy, I know that I can’t get across their tone of voice, or give every bit of background about their situation, so which quote I pick really matters.

I’ve written a fair bit about young single mothers. Asked why they got pregnant, why they chose to keep the baby, how they manage. And sometimes you’ll get a teenager replying along the lines of: ‘Some girls do get pregnant to get a council house, yeah, absolutely.’

What do I do with that? I know those words will make a strong headline. But if I use them rather than the less instantly “good value” comments, I don’t do this young mother’s entire situation justice. So I will think very, very hard about how to treat that kind of quote, and whether to include it at all.

Occasionally, I do stuff I know an editor wouldn’t like. National news organisations do not give interviewees the chance to see or approve copy before publication. There are practical reasons for this – deadlines, for example – but mostly, it’s about retaining editorial independence. Otherwise people ring up and say, “actually, I’d prefer it if you didn’t write about such-and-such a thing I told you about, it’ll make life really awkward.”

That, I’m afraid, is tough. If you don’t want me to write something, then don’t tell me, or alternatively, negotiate when you want to go off the record carefully and in advance.

But when a charity puts me in touch with someone struggling to rebuild their life, and they talk frankly about the hell they’ve been through, I’m aware a clumsily phrased comment about their situation could knock their confidence at best and make life even more difficult for them at worst. So sometimes I will read back quotes to an interviewee to make sure I have accurately reflected their views and they’re happy to go public with them.

On one occasion, I spent an afternoon with a young recovering drug addict who had spent four years on the game to fund her and her former boyfriend’s habit. She’d had her eldest daughter taken from her by social services: now pregnant again and with a new partner, she was on track to being allowed to keep her baby.

Given what she told me about the horrors of her previous lifestyle and job, I don’t know how she’d found the strength to kick her habit, but I was damned sure that nothing I wrote was going to set her back. The finished piece was written entirely in the first person; the risk of misrepresenting someone when you do this is real, no matter how good your intentions.

So I sent her the finished piece to look at. In this specific situation, editorial independence wasn’t going to trump her right to have her life described accurately and in a way that wasn’t going to put her recovery at risk.

Unlike many ‘important’ people who cavil at tiny bits of phrasing, this woman didn’t ask for a single change. And when my editor told me to go back and ask her a question – how much did she charge for each particular “service”? – (something I regard as the low point of my journalistic career) she didn’t get offended or slam the phone down. She told me. And, as I was finishing the call, she said thank you.

I loved doing that piece of work. The access and insight journalists get is central to why I am still entranced by this job.

But returning to my original question, does this kind of journalism change anything?

Well, that piece was published in The Times. A lot of people would have read it. The charity that supported her would have got some publicity.

What they really needed though was money to support more girls as they tried to get off the game. Maybe the piece helped them twist a few funders’ arms. Whatever it did, it’s nothing in comparison to the work done by dedicated experts at the coalface of disadvantage, poverty, suffering and violence.

When I try to answer the ‘does it make a difference’ question, I feel a bit like when you donate to charity online. Do you pick £2, £10, £25 or a bigger sum that means you won’t be able to buy that dress you had your eye on? Whatever you put is something, but it’s probably not as much as you could have given, and it’s certainly never enough.