Leafy and affluent are default shorthands when describing the English county of Surrey, but the council ward of Westborough, Guildford, has the highest number of young people who are not in education, employment or training (NEET) in the county. Child poverty is high in Westborough, and around a quarter of all female prisoners in the UK are in custody in Surrey, including a number of lifers at HMP Send.

While the cash-strapped Tory-run council recently grabbed headlines with a threat to raise council tax by a huge 15% , this has done little to shed light on the social needs that exist in Surrey.

The issue of how Surrey’s general wealth hides specific pockets of deprivation is outlined in a new report into the social and community impact of Watts Gallery Artists’ Village (WGAV), in Compton, about a 10 minute drive from Westborough.

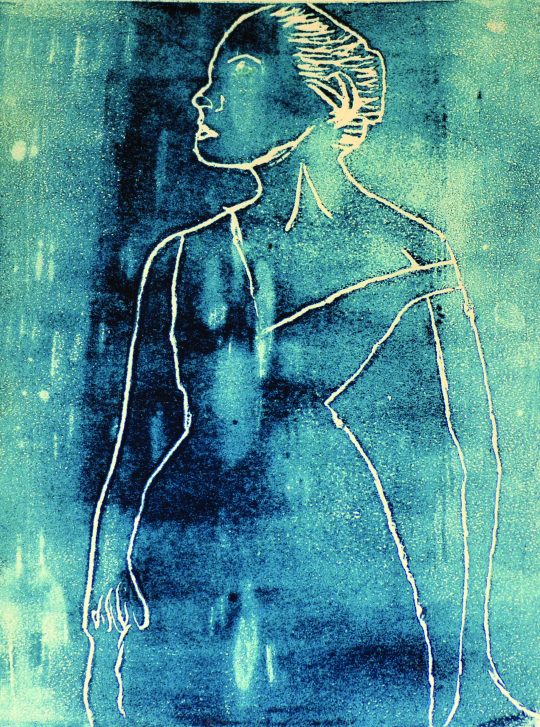

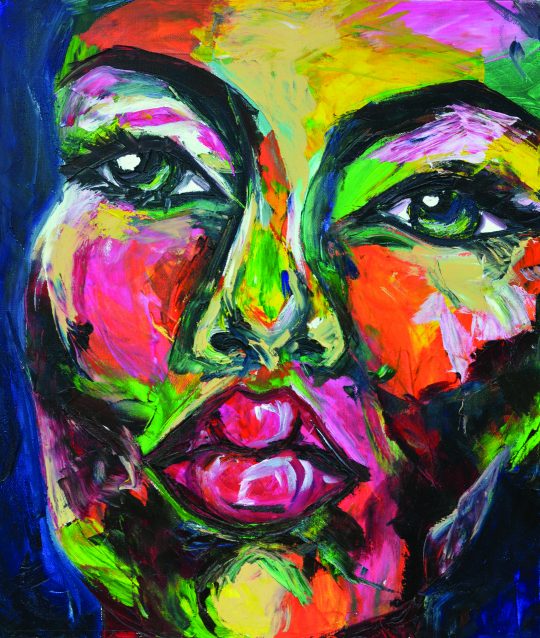

The gallery, opened in 1904 and dedicated to the work of Victorian artist George Frederic Watts, aims to transform lives through art – “Art for All” (Barack Obama, among others, has cited Watts as an inspiration). The report, Art for All: Inspiring, Learning and Transforming at Watts Gallery – Artists’ Village, describes the overlooked needs. It underlines the organisation’s role, for example, running artist-led workshops with prisoners and young offenders – I’m sharing some of the works here – as well as community projects, schools and and youth organisations.

There are, as the report states, six prisons situated within 25 miles of the gallery, including two for young offenders and two for women. More than 420 prisoners and young offenders took part in workshops over the least year and WGAV has had an artist in residence at HMP Send for over 10 years.

The report has been commissioned by Watts Gallery Trust and written by Helen Bowcock, a philanthropist and donor to WGAV and, as such, a “critical friend”. Bowcock argues that, despite the impression of affluence, Watts Gallery – Artists’ Village “is located in an area that receives significantly less public funding per capita than other areas of the UK”. The argument is that local arts provision in Surrey depends more on the charity and community sectors and voluntary income than it does elsewhere in the country (the concept that philanthropy, volunteering and so-called “big society” – RIP – only works in wealthy areas is something I wrote about in this piece a few years ago).

As public sector funding cuts continue and community-based projects are further decimated, Watt’s words are as relevant today as they were during his Victorian lifetime: “I paint ideas, not things. My intention is less to paint works that are pleasing to the eye than to suggest great thoughts which will speak to the imagination and the heart and will arouse all that is noblest and best in man.”

More information on the gallery’s community engagement and outreach programme is here.