The Tale of Laughing Boy from My Life My Choice on Vimeo.

This weekend, I watched a film that should never have had to be made, about a young man who should never have died, featuring people who should never have experienced what they’ve been through.

If you follow this blog regularly, you’ve probably already seen the powerful film, The Tale of Laughing Boy, which was released on Saturday.

If you haven’t seen it then, for the reasons stressed in my opening lines, please spare 15 minutes to watch it.

Better still, watch, imagine and act, as the film’s concluding message urges its viewers.

The film is about the life of Connor Sparrowhawk (aka Laughing Boy). Connor, who had autism, a learning disability and epilepsy, was 18 when he died just over two years ago in Slade House, an assessment and treatment unit run by Southern Health NHS Foundation Trust.

He drowned in the bath on 4 July 2013, an entirely preventable death, as proved by an independent report demanded by his family. I covered the family’s experience here and if you don’t know his mother Sara Ryan’s blog, these extracts published in the Guardian reflect a little of what the family has been through.

Two years after Connor died, the family is still waiting for answers, a police investigation is ongoing and the outrage over his death has led to a powerful campaign, Justice for LB. It has also driven proposals for a new bill to boost the rights of people with learning disabilities and their families (see also this brilliant gallery featuring artwork created as part of the campaign).

The Tale of Laughing Boy should be required viewing for – well, for everyone, actually.

The issues it raises touch not just families of people with learning disabilities or people with learning disabilities themselves. The film is relevant not simply to professionals who work in health and social care or to politicians and policy makers who focus on these areas. In fact, Connor’s story begs the question of how society values (or rather, undervalues) people with learning disabilities and how we, as a collective bunch of human(e) beings, can (and should) positively respond.

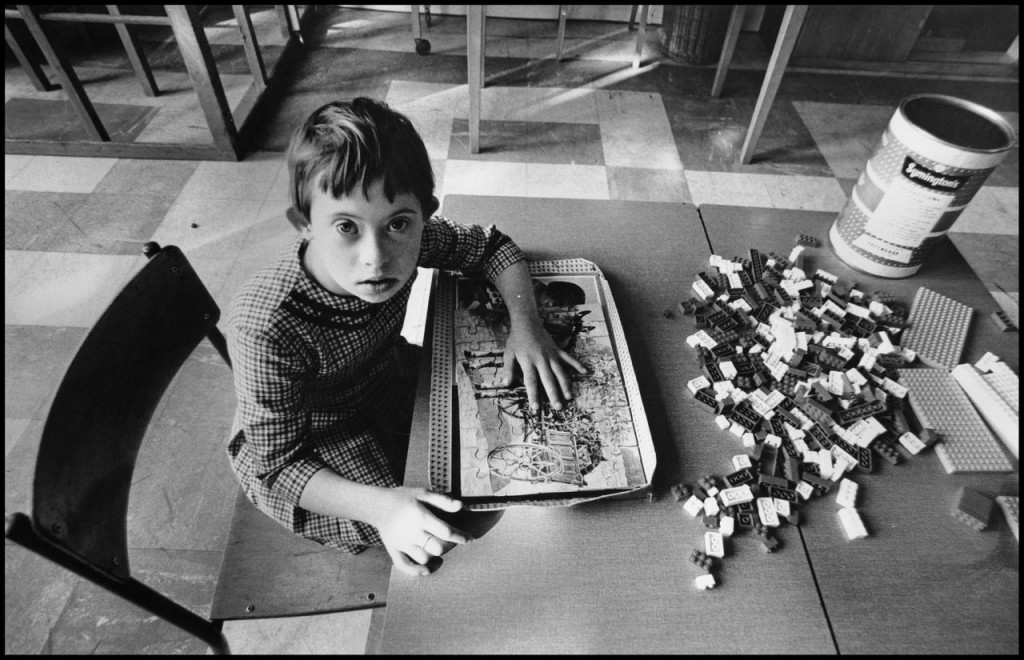

The film, produced by self-advocacy charity My Life My Choice and Oxford Digital Media paints a warm, affectionate picture of Connor from childhood to young adulthood. Interviews, photographs and home movies celebrate Connor’s life as well as demanding answers about his death. It is a short, clear, accessible, arresting film – warm, beautiful, funny, and moving.

Connor’s family and friends speak with searing honesty about about the impact he made on their lives, and about the difficulty in his support (which is what triggered his admission into the unit). The teenager emerges as an engaging, entertaining, popular young character with a love of humour and a passion for music and buses.

Inspiring and amusing anecdotes show how much loved Connor was and is by his parents, siblings, grandparents, friends and support staff; one of his brothers recalls Connor’s claim that their mother was breaching his human rights by getting him to do the washing up.

Rich, Connor’s stepfather, describes the proposed new bill that the Justice for LB movement has sparked.

Rich explains that the objective is “to change the way in which the law works…At the moment local authorities and the NHS and other providers can pretty much put people where they want, what our bill proposes is that you simply will not be able to do that you will have to take full regard of the individual’s desire and wishes into account before making them a placement in residential accomodation…the bill tries to at least ensure or encourage that the knowledge, the love, the affection, the care, the experience that families have isn’t ignored by providers and is a full part of the process”

As Connor’s mother Sara says, it is “shameful” that there is a need to campaign “to give a certain set of people the same rights as everybody else”. Her son’s death, she adds, was terrible, wasteful, careless and preventable.

I wasn’t able to attend the launch of the film but Kate at My Life My Choice was kind enough to ask two of the contributors to the film, Tyrone and Shane, both of whom have learning disabilities, for their thoughts so I could add them to this post. Tyrone said: “Connor was a happy person – always talking about buses. I feel sorry that he died and wish it didn’t happen.” He also said that “taking part in the filming was fun.” Shane just wanted to reiterate “It’s terrible that this happened.”

In the film, it is another My Life My Care trustee, Tommy, who makes a powerful statement of the obvious; someone with epilepsy should never have been left alone in the bath. He says simply: “It’s not rocket science”.

* You can read more here and follow the Justice for LB campaign on Twitter.