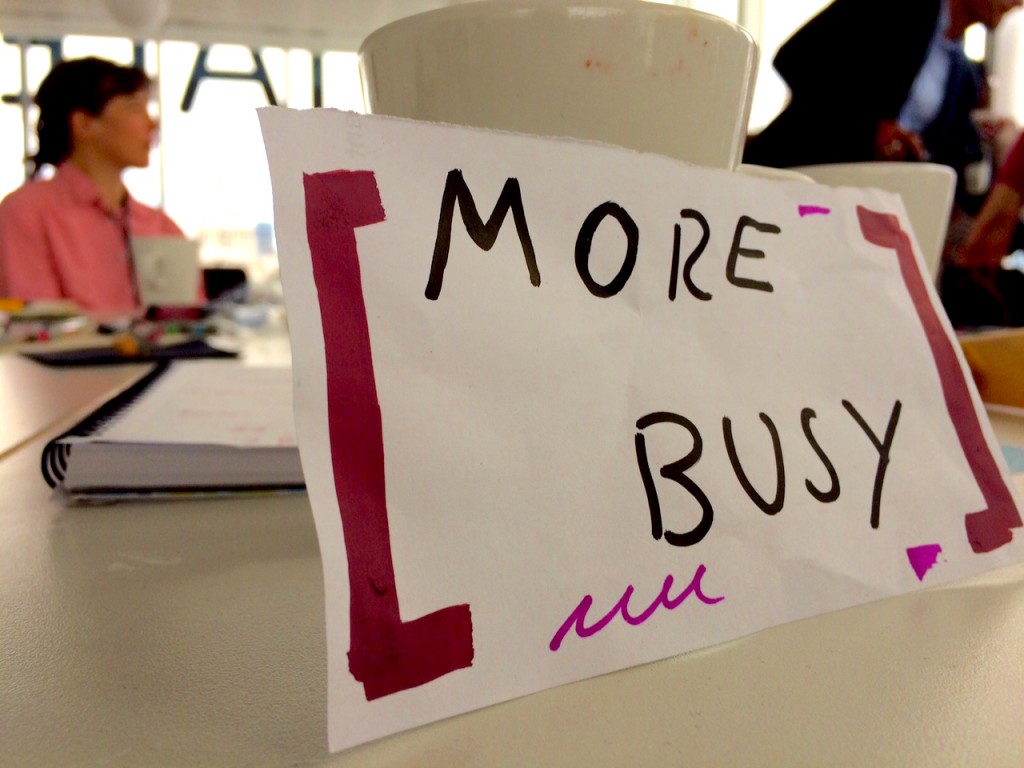

“More busy”. This quote from Kelvin Burke of Rocket Artists reflects what people with learning disabilities need in order to be more included in society; people want to be busier with opportunities to do, make and see more things, to have more time to spend with people (incidentally, that’s people who hang out with you by choice and because they share your interests, not simply because they’re paid to support you).

Kelvin shared his words at a Tate Modern seminar on inclusive arts that I was involved in earlier this week. The event’s title – “a research discussion bringing together practitioners and academics to explore issues around inclusive arts practice” – doesn’t do it full justice.

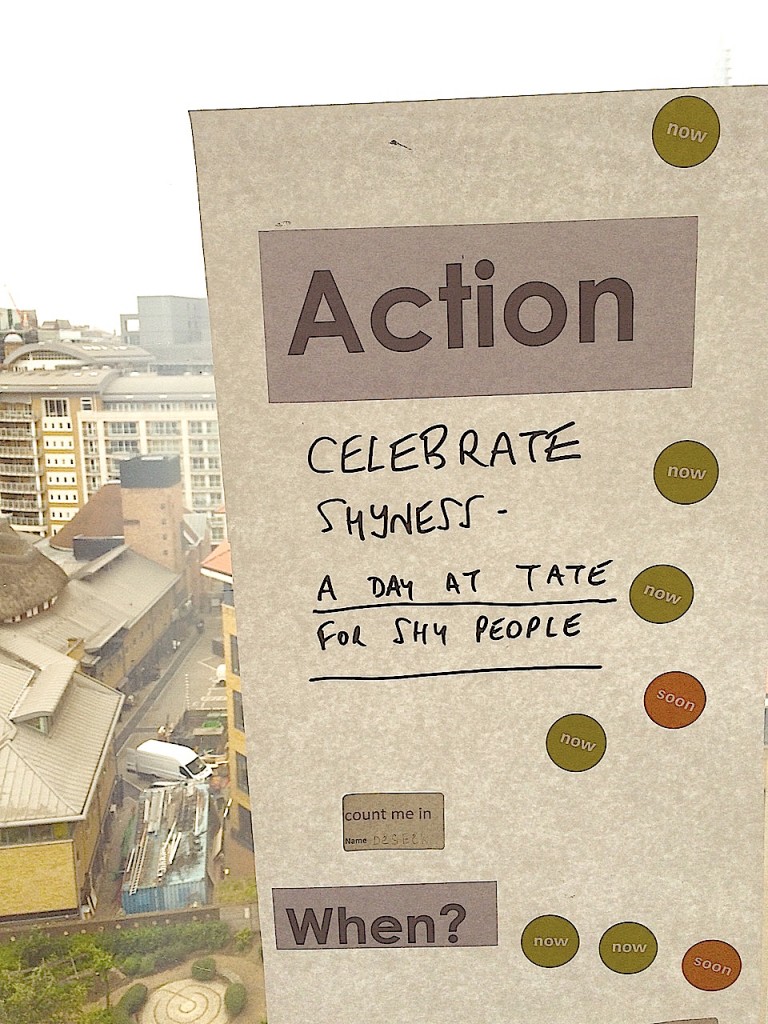

This engaging, creative, interactive, collaborative and fun event (yes, fun! There was golden ink! Stickers! Sewing patterns! And cake – both drawn and real!) encouraged participants (academics as well as artists and performers with learning disabilities and without) to explore the barriers to social inclusion, within the context of the arts sector.

People on the table I chaired talked about what stopped them from being more involved in society as well as what needs to happen to change that.

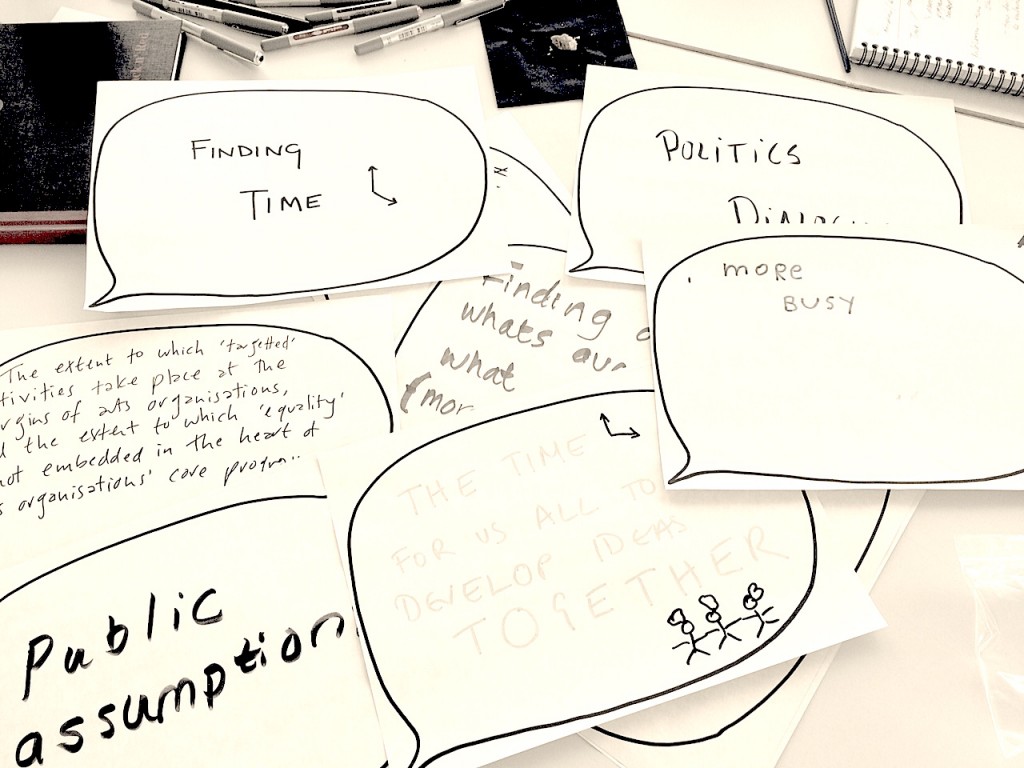

Although these issues are something I’ve looked at before (see, this piece or an opinion piece here about the unequal treatment of learning disabled people), until Monday I’d not explored them with marker pens, golden ink, coloured stickers, gargantuan Post-it notes, A4 size speech bubbles and dressmaking patterns.

But there’s a first time for everything (and now I only ever want to write in golden ink).

More seriously, the method and materials were necessary if the discussion about access and inclusion was to be accessible and inclusive, so everyone had an equal opportunity to contribute thoughts, words, doodles and designs.

I can’t faithfully describe all the challenges and solutions identified in a room buzzing with the ideas of around 50 people, but a few ideas are captured in the images on this page. (unfortunately I wasn’t able to take a shot of the “Bolloxometer” designed, I believe, to slice through meaningless rhetoric purveyed by those in authority, but I’m first in the queue for this should it ever go into production).

Time was, however, a big theme for discussion. Those who work with people who have learning disabilities said they wanted more time for sustainable projects (rather than be caught in commissioners’ and grant-makers’ short-term funding cycles). People with learning disabilities said they wanted more time to do things they enjoy, as Kelvin said.

Words like “equality”, “access”, “value” and “listen” cropped up a lot. As did the importance of celebrating differences and valuing people for what they can do, not defining them by what they can’t. While the challenge of funding and cuts (both to social care and the arts sector) was a major concern, people were generally unwilling to focus on money alone as a problem or solution, when so much rests on changing the perception of people with learning disabilities.

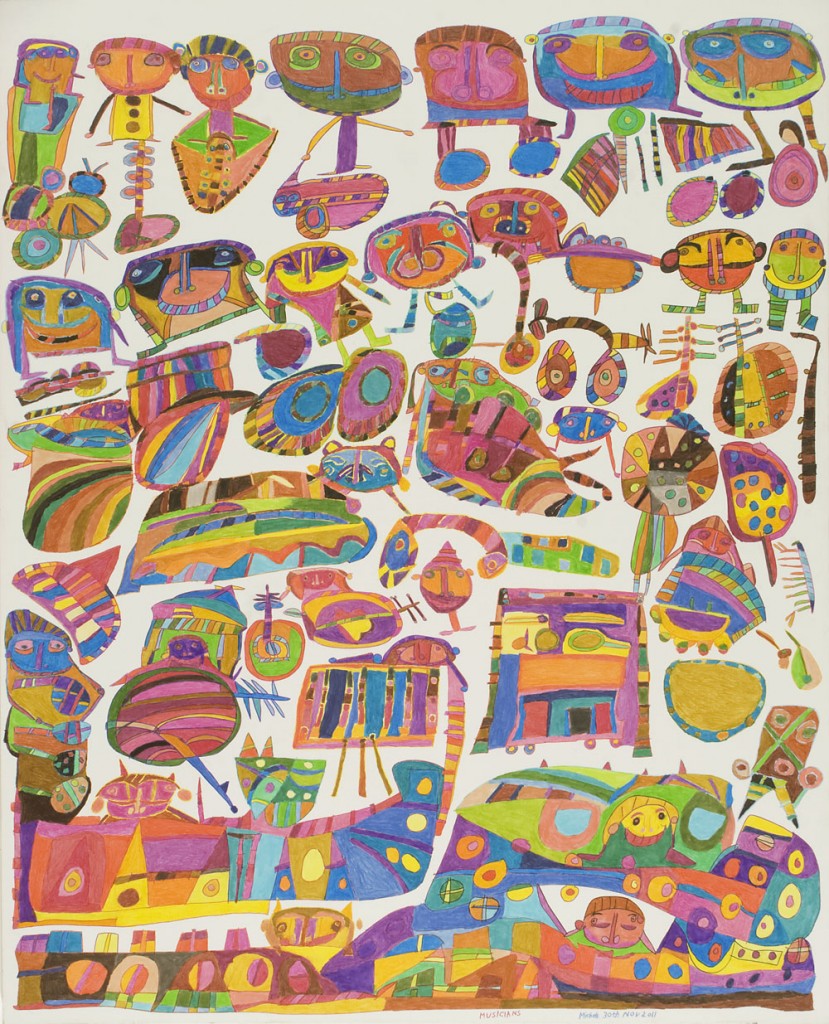

Rocket Artists performed towards the end of the day, captured in this lovely shot shared on Twitter by Brighton arts organisation Phoenix:

Rocket artists @Tate . All tied up. Great way to promote inclusive arts practice. pic.twitter.com/6B4SsD44ie

— Phoenix Brighton (@PhoenixBrighton) June 1, 2015

The event also included the launch of a thought-provoking and beautifully produced new book, Inclusive Arts Practice. Authored by the University of Brighton’s Alice Fox (also artistic director of Rocket Artists) and Hannah Macpherson, it was created through interviews with and guidance from learning-disabled and non-learning-disabled artists. The book looks at inclusive arts – defined as “creative collaborations between leaning disabled and non-learning-disabled artists” – and its “socially transformative potential for collaborators and audiences”.

It addresses difficult questions, such as the differences between art therapy, occupational therapy and inclusive arts and clearly sets out the practical steps to create more collaborative art. The book acknowledges the fact that the term inclusive arts “presupposes exclusion” and asks how such collaborations between artists of different abilities can have real, cultural value (something I’ve blogged about before and which the Creative Minds project is exploring).

The book makes a persuasive case for everyone to have a cultural life in their communities; Southbank Centre director Jude Kelly, for example, comments in the book on how “we believe in cultural rights as a profound part of human rights”. Creative collaborations with the use of time, trust, skills and choice, are presented as “a force for societal good”:

“People with learning disabilities tend to be undervalued members of society, are much more likely to live in poverty, and are much more likely to suffer hate crime than their non-disabled counterparts. It is estimated that around 1.5 million people in the UK have a learning disability and over 3,000 of these people have spent over a year in an ‘assessment centre’, often a long way from family, and which is not designed to be a permanent residence. Many people with learning disabilities do not have access to any regular creative leisure activity outside their residential environment, despite the proven benefits of such activities for health, well-being and resilience…”

Inclusive arts can make audiences “feel differently about the people whose work they see and they can feel differently about themselves”, that is one powerful message in Inclusive Arts Practice.

Which is why the inclusive arts movement has an important place when it comes to equality for people with a learning disability. “We want greater powers to be seen, to vote, to be included, have the same opportunities in social life, education and employment as everyone else,” as campaigner Gary Bourlet says, or as the rights set out in the campaigning LB Bill show).

As for the sewing pattern that everyone contributed to on the day, one stylish spark made the beautiful observation that the final garment, emblazoned with words and images setting out some ways to break down social barriers, should have a sliver lining; the team from Brighton now plans to make the dream coat a real life action mac.

I can’t wait to see it.