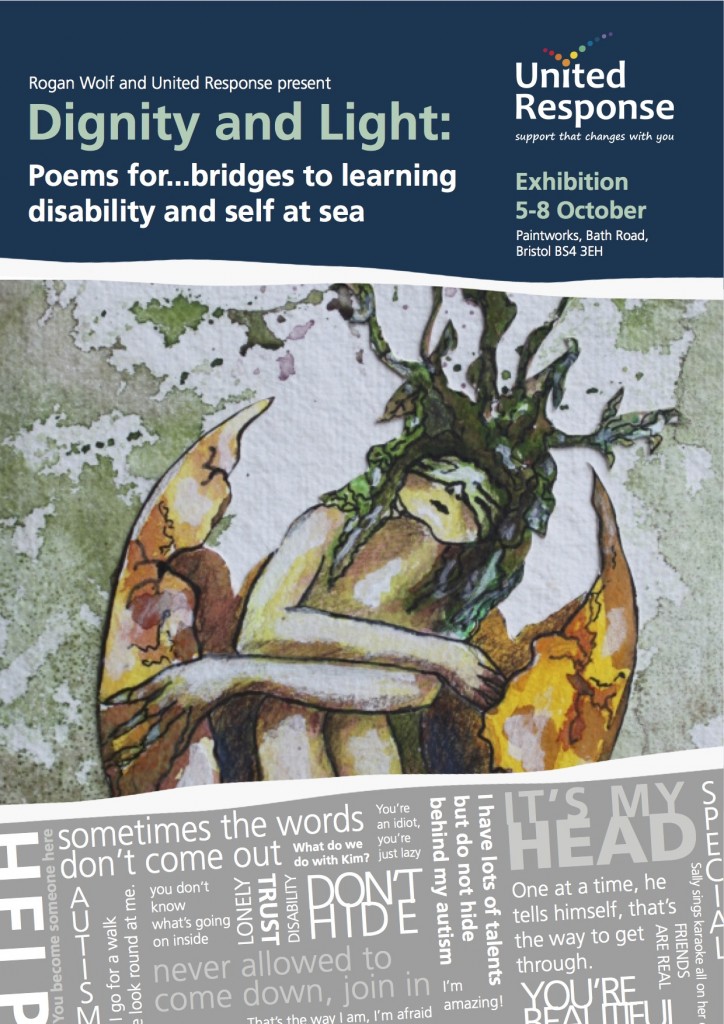

A poetry exhibition opening today aims to challenge attitudes about learning disability and mental ill-health.

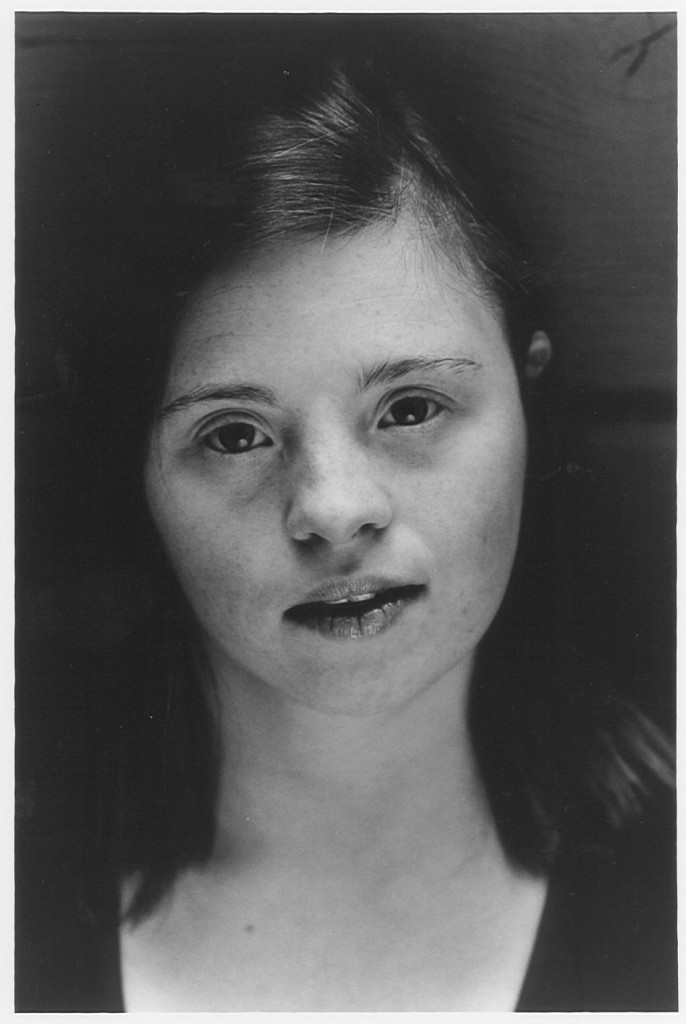

The learning disability poems are partly a tribute to the late Kim Wolf, who had Down’s syndrome; the collection includes writing inspired by her and which reflects her perspective on life.

A collaboration between Kim’s brother, former mental health social worker and poet Rogan Wolf, and disability charity United Response, the exhibition, entitled Dignity and Light, aims to “address and challenge the stigma and stereotypes and fears still associated with learning disability and – even more – with mental ill health”. As Rogan explains: “If I can see what life is actually like for you, then I am more likely to recognise and not just dismiss you”.

The poetry has been “written with, by and about people with learning disabilities and mental health needs” (United Response explains more of the background to the project here).

The poems, part of the Poems for project that supplies poem-posters for public display free of charge, are on display at Bristol’s Paintworks from today until Thursday. The collection will then be available online, as an illustrated book and, it is hoped, used in schools to raise awareness.

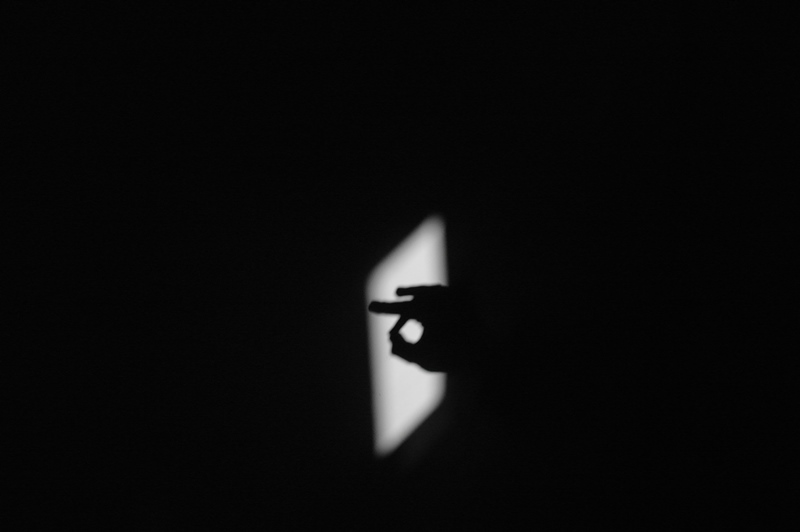

Rogan says of the project’s aims: “There is still this common urge to treat people who are in some way ‘different’ as dangerous aliens, or objects of scorn or mockery, people we need to keep separate. Thus, learning disability and mental ill-health are both experienced by a minority of people in our society and, though the experiences are very different, the stigmatisation both can meet is the same. It cripples lives. It shuts them off.”

While acknowledging that poems are no substitute for policy or resources, Rogan says “they can connect and can enlighten”: “Politicians keep emphasising the urgency of the need for better mental health services and better understanding – I suspect to relatively little effect. There is a crisis here and it just continues. And reports keep emphasising the need for better mental health education and resources in schools, so that children already struggling can seek help at an early stage…[the poems] can help children who are struggling recognise what might be happening and what might help.”

The collections draw on poetry written or collected over the last four decades including through Rogan’s work, personal connections, creative writing workshops and the Postcards from the Edge project run by United Response.

The poem “Other People” by Shiraz, who is supported by United Response, was part of the postcards campaign: “People are like apples or eggs. They look all right on the surface, but you don’t know what’s going on inside.”

In another poem, “A father to his son (with Down’s syndrome)”, the author, John Mclorinan, describes his child as “wonderfully irreverent, irrelevant, inappropriate, spontaneous, topsy turvey, upside down. vulnerable, perceptive, aware, eager to communicate, willing to please”.

The collections that launch today, writes United Response’s director of policy Diane Lightfoot in the illustrated book that contains them, “shine a light on those who too often remain unseen in the shadows and on the fringes of our society”.

The poem below is by Rogan, written from the perspective of his late sister Kim. The poet explains: “We often went out together. Some of the words and phrases above are Kim’s own. Somehow she had to make sense of the way people looked at her, in the street, or when she entered a public room.”

Shall we go for a walk ?

When I go for a walk people look round at me.

Will you come too ?

Will you hold my hand ?

They look round at me. There’s something wrong.

Will you come too ?

Perhaps I’ll put my ear-phones in and play my music extra loud.

I am going for a walk. What’s wrong ?

Will you come too ?

Will you hold my hand ?

* See Poemsfor.org to read more or read about the exhibition opening times here.