Around 49% of disabled people in the UK aged 16–64 are in work, compared with 81% of non-disabled people, according to government figures.

The government has said it wants to narrow this gap (the figure has remained the same for decades) but at the same time its various policies and cuts relating to disabled people undermine this aim. A recent government green paper on work, health and employment, proposes to help at least 1 million disabled people into work, but has met with a lukewarm response from campaigners.

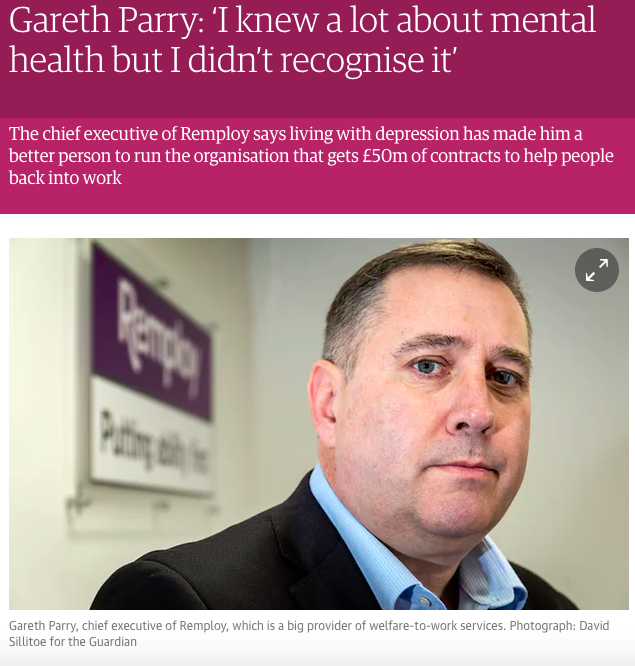

This was the context to a recent interview with Gareth Parry, the chief executive of employment organisation Remploy, which has £50m of contracts from central and local government to help disabled people get jobs or support them back into work.

Parry, who worked his way up Remploy after starting as a trainee almost 30 years ago, has depression, something that he says gives him a more personal insight into his job running employment support organisation (“It reinforced the importance of organisations like Remploy; work gave me routine, structure, focus, when everything else in my life was in chaos”).

He is a forthright speaker about how his personal experience influences his role at the helm of an organisation aiming to support people with mental health issues; he wants more senior executives to be open about mental ill-health, for example.

The organisation, however, has its critics. While Remploy was launched by the postwar government in 1945 to give disabled second world war veterans sheltered employment, the last factories closed in 2013 in line with the idea that mainstream employment was preferable to segregated jobs. Yet many felt the closures abandoned disadvantaged people.

More recently, in April 2015, Remploy was outsourced to a joint venture between US-born international outsourcing giant Maximus – which has come under fire as the provider of the Department for Work and Pensions’ controversial “fit for work” tests – and Remploy’s employees, who have a 30% stake in the business. Critics say that being owned by Maximus undermines Remploy’s status as a champion of disabled people.

Parry rejects such suggestions: “I can understand why people would see it that way, but we have a strong social conscience, the employee ownership keeps us focused on that, the profits don’t go overseas to America, they go back into the [Remploy] business.”

Longer term, Parry believes Remploy could take on international work, like advising other countries on closing sheltered factories. He adds: “Our mission around equality in the workplace has always been and is within the confines of the UK, but if we want to make a real difference in society in the UK, the opportunity we have now is to say ‘why stop there?’” Future issues in employment support, he adds, include sustaining an ageing workforce, with help for issues like dementia in the workplace and other age-related conditions.

In terms of other changes, Parry’s words on the rise of online support (as opposed to face to face advice) reflect a general trend towards more online and digital support: “I’m not suggesting online will replace face-to-face services, but the idea of giving the power of choice to the individual as to how they access services is meaningful”.

Remploy is almost unrecognisable in terms of its remit, ownership structure and operations since its inception more than 70 years ago; as the government and local government contracts on which it once relied are dwindling, it will be interesting to see where the next few years take Remploy – and, most importantly, those it helps.

The full interview is here.