This is one question that Venture Arts (VA) and our speakers will be asking the heritage and cultural sectors at our symposium, Making the Case, at the Grand Hall, Whitworth Art gallery on the 25th May. VA is an organisation that specialises in visual arts in the North West.

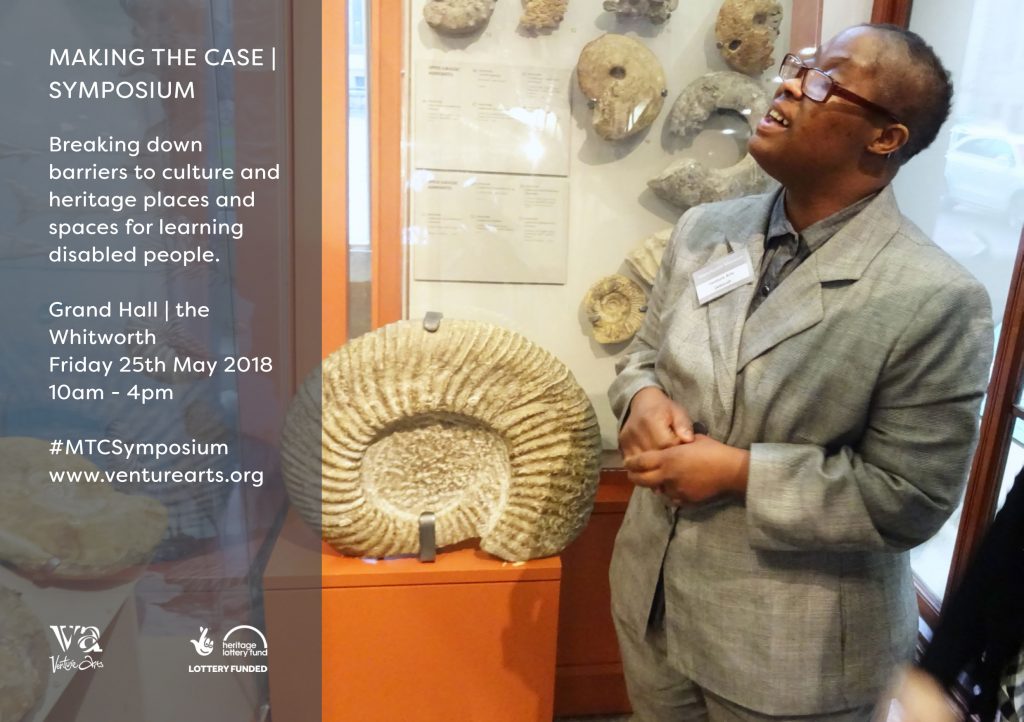

“People with autism can do things like other people that don’t have autism in society. Society should be more accepting of people and not assume people can’t do things.” This is what Amber Opka Stother says – Amber (pictured above) chairs the VA steering group, has worked at Manchester Museum and arts centre HOME Manchester and is an ambassador for learning disabled people in the heritage and culture sector.

Our symposium will showcase the experiences of learning disabled people who have formed VA’s Cultural Enrichment Programme, funded through the Heritage Lottery Fund. The programme has seen over 20 people undertake 16 week work placements in some of Manchester’s best known cultural and heritage venues.

On the day we will also be seeing and hearing about other projects from across the country and highlighting areas of best practice.

“Unfortunately, our experience shows that people often don’t feel that big cultural institutions are for them or know how best to welcome people into their buildings. In my view we need to see more learning disabled people working within culture to be able to start to overcome this and make real change happen”, says Amanda Sutton, VA director.

This kind of inclusion makes sense, adds Amanda: “You are going to feel much more comfortable about going into a building, that can otherwise feel quite austere and foreboding, if you can relate to and identify with the people welcoming you and working within the venue.”

In 2015, researchers Lemos and Crane looked at learning disabled people’s access to museums and galleries (pdf). It stated: “Despite longstanding commitments to access, participation, learning, equality and diversity, museums, galleries and arts venues are not currently required by funders or policy makers specifically to promote access for people with intellectual disabilities as they are in relation to other groups…Mainstream arts organisations did not seem always to have a clear framework of good practice for improving access for people with a learning disability. This was perhaps the consequence of widespread uncertainty and anxiety among those with little personal or professional experience of people with learning disabilities.”

So Venture Arts aims to rectify this through working with cultural institutions to introduce learning disabled people to every aspect of their working operations. We reckon that if we can get people in “through the back door”, they will gradually change attitudes and integrate into institutions. Through our work so far, this has indeed happened. People have been back stage, in the conservation rooms, behind the scenes, delivering tours, in museum shops, in the staff room and are now well known by all the staff and visitors alike.

Here’s what Amber thinks about her experiences with VA so far:

At Manchester Museum, I volunteered and worked in the shop and in the postroom and in the vivarium as well. I ended up doing a tour for my friends and family which they really, really enjoyed, it boosted my confidence about speaking to people. It was really nice meeting lots of new people I did things that most people don’t . It’s nice to see the different parts of the museum.

People were, very welcoming and I think I am helping them to learn more about working with people with autism too, maybe like how people communicate or something.

Now I’ve started a new placement at HOME, an arts centre, which I’m really enjoying. We get to go behind the scenes and see how the cinema works which is really interesting and we have worked at the front of house and we get to see some free shows as well and that’s really, really good.

I think it’s important to have people with autism working in these places to see what great skills people have and how it makes a difference to volunteering. They will be more interested in employing people with autism, it will make a big difference.

On a personal level, it has helped me to be more confident and it’s helped me to become more confident in doing other jobs and things. I also work in a school and this experience has influenced how I am with the children, I feel more confident because I had to speak to people and that has lifted my confidence.

Last year I also delivered a workshop about making galleries accessible at a conference called Creative Minds and I loved every minute of it. I probably wouldn’t have been able to do this if I hadn’t worked at the Manchester Museum beforehand. There were a lot of people there too so I was really happy with myself.

I’m really looking forward to the symposium at the Whitworth as well and to interviewing people from museums and galleries. I’m going to interview them about the job and what we do. It will be really important to come to the symposium because you will get to hear about the great work that museums do with people with disabilities.

Even though I’ve got autism I try and do things that people without autism think that people can’t do like drive, I’ve passed my driving test that was a big achievement for me because I’ve always loved cars. People with autism can do things like other people that don’t have autism in society. We need to celebrate difference and make sure that people recognise what great things people with disabilities can do. I get upset sometimes if people don’t understand me, like my driving instructor who didn’t think I could pass my test. It’s important to listen so people can know what message people are trying to get across.

My advice for other museums? People have really great skills and they should give people the chance. People with disabilities can be really good at doing lots of great things and have skills that other people without a disability might not have, which can be valuable in a workplace. For example, people can be more understanding of other people.

It would make me happy to see people with disabilities working in museums because it’s good to see people with great skills doing a good job. If people give them a chance it would be a great place to start when people don’t feel comfortable about going into a museum.

Barriers for learning disabled people in going into a museum can be the staff of a museum because they might be a bit rude towards them or can’t understand if someone has no speech or something. It might not have a ramp or the lift might not be working or someone might be deaf as well so that could be a barrier. Museums should be more accessible to people with disabilities and people should make sure they don’t put jargon and put language that people understand on their walls.

I’m looking forward to the 25th to hear about what people are going to say. I’m looking forward to meeting everyone and to what people have to say about their experiences at the museums and it should be a great day.

Find out more about the Venture Arts symposium here or follow on Twitter, Instagram or Facebook.

Above, a poster designed by a child in Stoneyburn, West Loathian, speaks directly to the community.

Above, a poster designed by a child in Stoneyburn, West Loathian, speaks directly to the community.