Last summer’s riots, which began a year ago today, hardened my resolve to write an uncompromising book, British Voices, about our country from the perspective of its people. The comment above comes from a teenager I met in east London last August, not long after the end of the unrest.

The riots felt like an expression of something we had swept under the carpet. It seemed to me that failing to address the way that people in the country were feeling – including the sense that ordinary people’s voices often went unheard – would simply leave those feelings to fester once again. I wanted to approach the widest range of people possible and no matter they said, would present their opinions faithfully.

I started my research three weeks after the end of the riots. One of the first places I visited was Hackney, the scene of some of the worst trouble, and a lot of discussion focused on stereotypes of young people and a lack of opportunities.

“There’s a lot of talent in Hackney,” one young man suggested, “but there are no opportunities to uplift yourself. We’re left stranded; we have to fend for ourselves; so, if you see people with the nice car, you say, ‘I want some of that’. Our generation, we like fancy stuff but we can’t afford it – the riots were an opportunity to get things you know you couldn’t otherwise get.”

Was it worth the risk of a criminal record? “If there are no opportunities anyway,” he replied, “you might as well risk it.”

There was also anger towards the police. “They racially discriminate,” another young man said. “They search the black kids and leave the whites. They smashed my brother’s head against a windscreen, pushed me up against a wall, all for no reason. That’s why people rioted – they enjoyed having power over the police. They were saying, ‘If we wanted to take over, we could.’”

“It was great how youths were united by the riots,” one young woman said. “Gangs you wouldn’t expect to mix going up against the police together. It was great to see such spirit.” She went on: “It was wrong to burn people’s houses and family businesses, but the big shops all had insurance so what does it matter? I don’t see how it’s different from MPs and their expenses.”

I asked her whether the expenses scandal justified violence and looting. “No,” she said, “but it sets a bad example.”

It was an argument I heard again and again; indeed a sense of disillusionment, and alienation ran throughout the entire three months I spent travelling around England, Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales. I went as far south as Lizard Point in Cornwall and as far north as the Shetland Isles, talking to over a thousand ordinary people along the way. They were disillusioned with different things and expressed their feelings in different ways, but the feeling remained.

As I travelled, the anger in the wake of the riots seemed to fade. It was replaced by a sadness, a sense that for all the social, economic and technological steps forward the country had made, a lot had been lost along the way: a sense of community, trust and responsibility to one another.

The riots may prove to be a one-off, a few days of violence consigned to history; and even if there is trouble again, the police will be better prepared to respond. But none of the underlying issues have changed since the unrest began a year ago. Indeed, since then the economy has deteriorated and national institutions – the media, the police, the banks and politics – have all continued to take a battering. Surveyed around the Queen’s Jubilee, 75% of respondents to a Yougov poll said that community spirit had got worse in Britain, chiming with my own findings.

I came home determined to use the lessons I learnt to found a new charitable trust, The Community Trust, aiming to address this issue. My confidence comes from the most powerful lesson from my journey: that, in spite of all the changes in our society and the challenges we face, the kindness and decency of the British people lives on.

I also picked up some valuable lessons on the types of initiative that the new trust might support to harness that kindness and decency and to build a stronger society.

First, projects bringing together people from different backgrounds, building social bonds, fostering trust and breaking down barriers between communities. Second, initiatives enabling people to help each other to navigate their way in an increasingly complex, difficult world, building the skills, networks and personal attributes needed to get through and to thrive.

Small but important initiatives such as these – and the willingness of ordinary people to support them – could foster a greater sense of community and citizenship in Britain. That might not solve our problems, but might help us to face them together, rather than turning in on ourselves.

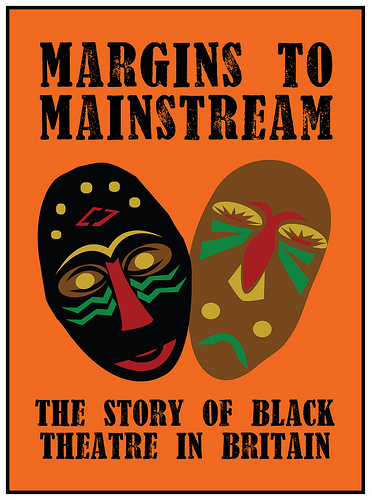

The term black theatre might conjure up images of a niche and very 20th century concept, but from

The term black theatre might conjure up images of a niche and very 20th century concept, but from