Happy New Year – and seeing as we’ve just had panto season (oh yes we have – sorry, couldn’t resist) here’s one fairy tale I wish would come true: Once upon a time, in a land far away, people who have a learning disability face don’t face discrimination, prejudice and abuse.

In reality over the last few weeks alone there have been comments from a former UKIP candidate that that mothers carrying foetuses with Downs syndrome or spina bifida should be forced to have abortions and someone from Mensa (the organisation for intelligent people) making what I can only describe as an unintelligent comment describing people with low IQs as “carrots”.

While my fairy tale sounds far fetched, there is at least a happy story emerging in the theatre sector, where venues and theatre groups are trying to be more inclusive of “non-mainstream” audiences.

Although theatre arts have long and well-documented therapeutic links to learning disability, what’s often lacking is understanding on the part of audiences and venues, as has been reported and and as I’ve had the personal misfortune to find out.

Which brings me back to panto, the latest theatrical genre to benefit from the burgeoning growth of the relaxed performance (see my last post on this back in October ).

You’d have thought that the slapstick shows, with their badwy humour, audience participation and rolling-about-it-the-aisles atmosphere is just about as informal a theatre experience as you can get, but even pantos can do with a more understading attitude to audiences that are different. Not only that, but often the noisy environment of panto is a huge challenge for people with sensory issues – you might want to take part in the family experience, but need time out to gather yourself if you feel overwhelmed.

Relaxed performances are aimed at families with children with autism or learning disability. There’s a more relaxed attitude to noise in the auditorium (staff receive training from the National Autistic Society) and before the show, audience members get detailed information and photos or might attend a “familiarisation meeting” in the theatre and make use of a chill-out zone during the performance.

Ambassador Theatre Group (ATG) announced pilot plans for relaxed pantomimes last year. Hopefully ATG will judge the scheme to have been a success and will embark on a relaxed panto performance at one of its West End theatres later this year.

My sister Raana had a great panto experience recently – it wasn’t because of the show itself, or because it was a relaxed performance (it wasn’t) but it because of how she was treated outside the auditorium, not just in it. A “relaxed performer” and understanding and accommodating staff, in fact, made all the difference.

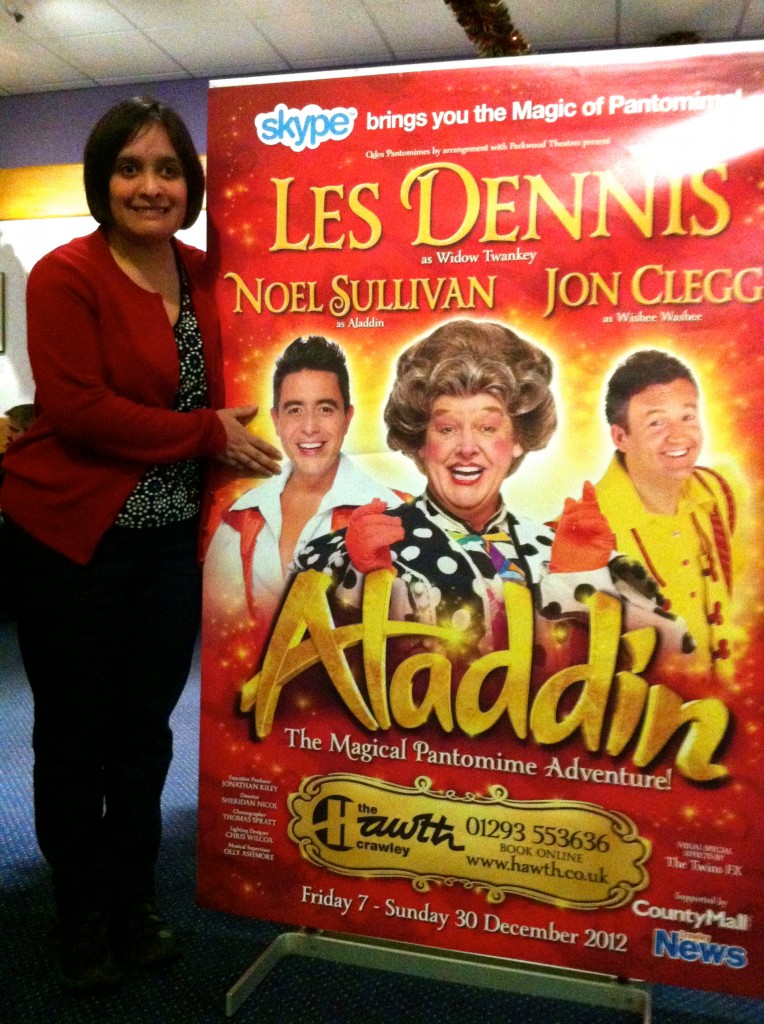

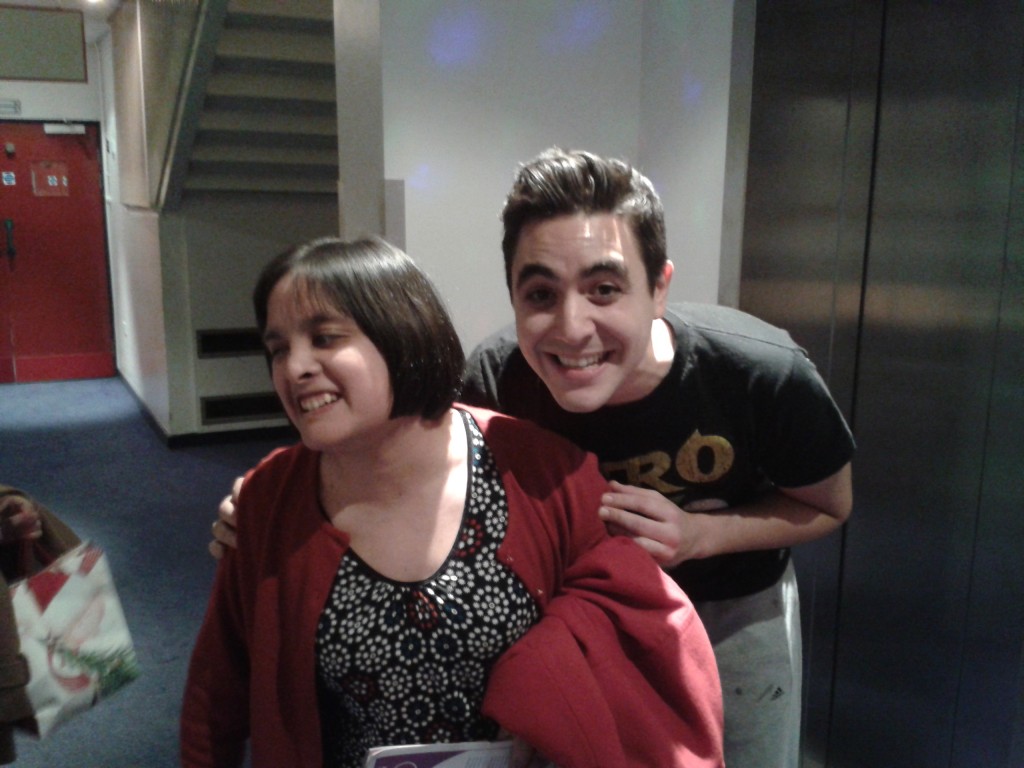

My mum took Raana to see her hero, singer Noel Sullivan (onetime member of reality TV pop group Hear’Say) peform in panto at the Hawth Theatre, Crawley. Raana was desperate to meet him; for 10 years or so she has listened to his songs, watched him on YouTube, seen his shows, always talked about meeting him but never quite plucked up the nerve to try, even after waiting backstage after a show.

She had a stage door opportunity once but bottled out at the last minute – as our teenybop hero turned musical theatre performer emerged from the exit, off Raans scampered down the road, leaving my 60-year-old mother brandishing a mug as a gift and an awkward smile.

But, hey presto, the long-awaited meeting finally happened in December, thanks to some understanding members of staff who accommodated her request (replying promptly and sensitively to my mother’s telephone calls) – and to an understanding performer who gave his time to a painfully shy, awestruck, silent, nervous, overexcited fan just minutes before the curtain went up. Her wish was granted and she was incredibly proud of “her moment”.

This time, despite the palpable anxiety, fidgeting and refusal to eat (nerves) she actually managed to meet him. As usual, my mother was prepared for her daughter to feel so overwhelmed that she’d throw up – despite this being something Raana desperately wanted to do. But it speaks volumes for my sister’s determination and self-possession that she waited patiently to meet him (I know we’re not quite talking about an audience with the Pope but with a man in pancake make up in Crawley – but the fact is she had this dream, and it was fulfilled).

Even weeks later, she is still buzzing from the experience, still mentioning to anyone who’ll listen (actually, even if they don’t listen) that she’s met her idol, still waving around her laminated (yes, for posterity) A4 colour copy of the photo of Noel posing with her.

This was, undoubtedly, her equivalent of Mission to Lars – only not quite as transatlantic, nor epic in scope, arduous in execution nor indeed as hardcore musically (just as well; I’m struggling to picture my mother at a metal gig).

This is what she said immediately afterwards (thanks to my leg man of a mum for taking down her verbatim words afterwards): “I met the biggest star in the world – couldn’t believe it was him! I got two big hugs from him and he posed for two photos with me. I was very happy to meet him. He is still my favourite!” (By the by, she is now planning her next meeting with him, rather than treating this as a one-off miracle, it’s boosted her confidence in the theory that her dreams can come true).

While the theatre in Crawley isn’t part of the relaxed performance scheme, general manager Dave Whatmore says that if someone needs a carer or companion – through having a visual impairment, learning disability or using a wheelchair – ticket concessions are available.

He adds: “Over the years staff have received training courses to raise their awareness of disability in general – although autism awareness as a specific training course hasn’t been offered, we’d certainly consider something for the future if it were available.” The theatre already hosts events for children with learning disabilities, working with Crawley council’s arts development team on organising inclusive events.

So while it’s heartening to see that the official relaxed performance drive is gathering apace, it’s also worth noting the difference that can be made through individual actions, good old fashioned customer communication, courtesy and simple awareness and understanding.

As for the days of people with learning disabilities being frowned upon in mainstream theatre, let’s hope they’re behind us (panto pun fully intended).

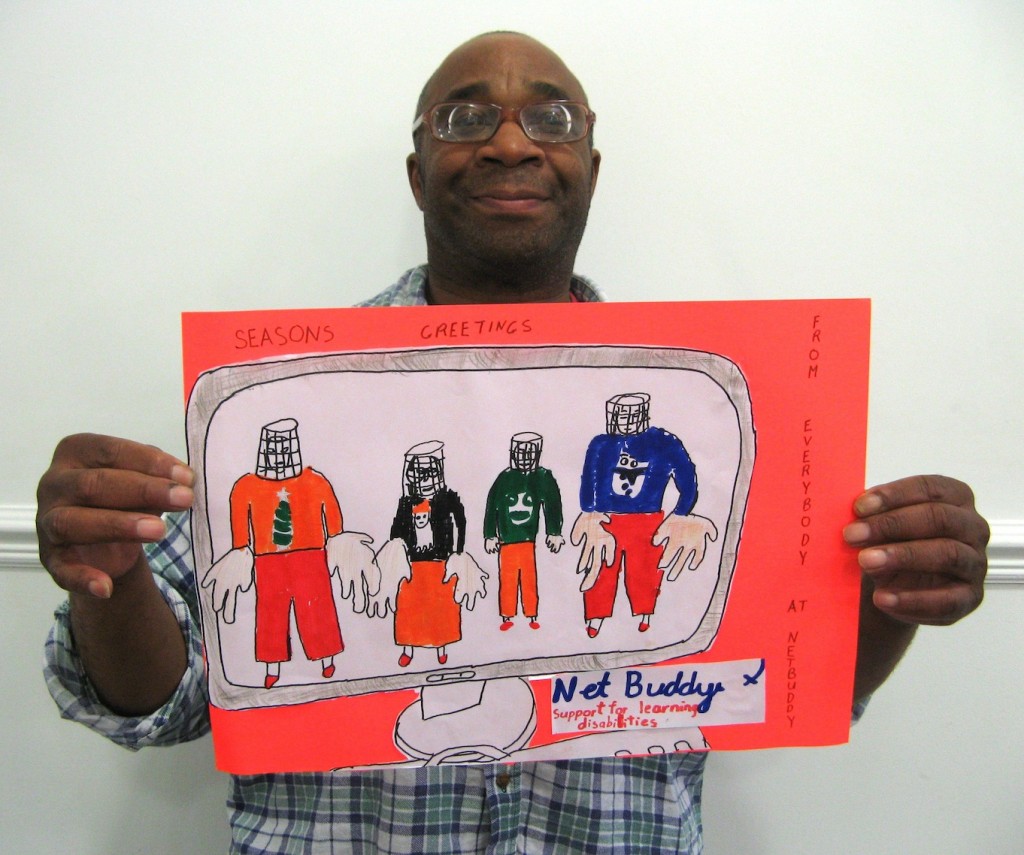

* For more information on accessible shows and venues, you can also checkout the Time Out with Netbuddy listings or follow @timeoutnetbuddy on Twitter

![robin[1]](http://thesocialissue.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/robin11.jpg)

![IMG_6065[1]](http://thesocialissue.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/IMG_60651-1024x716.jpg)

![IMG_8166[1]](http://thesocialissue.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/IMG_81661-1024x716.jpg)