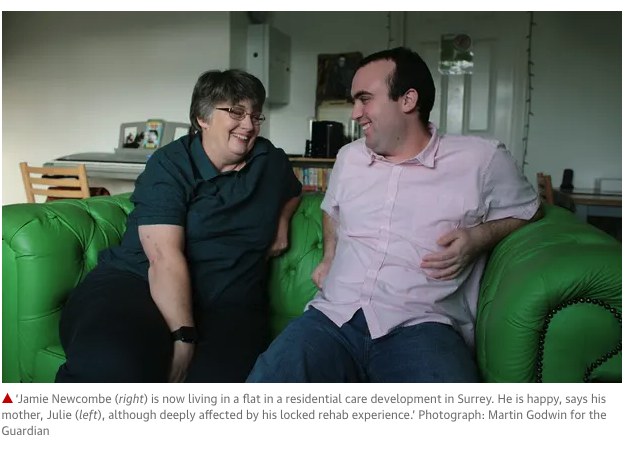

I love the photo, above, of Jamie Newcombe, taken by Martin Godwin for an article in the Guardian today.

Jamie, who has a learning disability, was once in a series of restrictive inpatient care units, including a stint in so-called “locked rehab” where he ended up with a broken arm (you can read more on his experience here).

Today. Jamie is proof that people can thrive if supported in the right way.

The government’s long-stated ambition is to move the majority of learning disabled and autistic people from inpatient institutions like assessment and treatment units (ATUs) into community-based housing. This has been the goal of its transforming care programme, due to end in March (and actually care in the community has been the goal of successive governments for decades..).

Transforming care was launched after the 2011 Winterbourne View abuse scandal exposed the reality of ATUs. The aim was to move all inpatients into community-based housing within three years. That target was missed and progress on moving people from ATUs has been slow.

Transforming care is ending soon but there are still 2,350 people in ATUs and there appears to be no replacement for the national programme. Instead, last week’s NHS long-term plan included a new target (by 2023-24) to reduce the numbers in ATUs by half compared to 2015 levels (when there were around 3,000 people in such units).

Campaigners have drawn attention to the fact that this new target essentially extends the original one.

Inpatient conditions for learning disabled people are also in the spotlight with a forthcoming government-commissioned review into restrictive approaches to learning disability care. In addition, similar issues are the focus of the parliamentary Joint Committee on Human Rights, which has recently been examining conditions in learning disability units.

As ATUs rightly fall out of favour, campaigners fear more people will be discharged from them into care that could be equally restrictive, like the sort of locked rehab unit that Jamie was in.

Jayne Knight has visited several locked rehab settings. Knight is an independent family advocate and founder of You Know, which helps people find community housing and care. She describes these “institutions in the community”: “There can be systems of going through one locked door after another. In some places, you are asked what is in your bag and it’s checked, people can still be restrained physically on the floor in their own homes.”

Knight recalls one six-bed facility for autistic people behind a padlocked gate at the end of a residential road, with two staff supervising each resident. She adds: “The number of people was overwhelming. There were narrow hallways and small rooms…It was noisy and the atmosphere didn’t feel calm. People shared bathrooms and so a very strict rota and timetable was in place to enable this.”

The rush to move people from ATUs is likely to have negative consequences, says Steph Thompson, managing director of Waymarks, a voluntary sector organisation supporting people from hospitals into communities. Thompson says: “Pressure to meet discharge targets is highly likely to have two unintended consequences. One, is putting people at risk through unplanned discharges into the community. The other, is step down or across into another ‘bed’. Both routes achieve the discharge target but neither is good for the person.” She adds: “If you have a performance target to meet as a commissioner and an agreed discharge date, it can feel safer to move someone into a ready built unit with a vacancy, health professionals and potentially a lock on the door. It fixes the figures. But it’s not transforming care.”

Another risk, says Lib Dem MP and former health minister Norman Lamb, is the revolving door of discharge and readmission: “There is a massive risk at the moment driven by the nervous pursuit of a target and a recognition that they have left it too late and if you rush to hit the target with time running out then the risk is you cut corners, you can discharge people unsafely potentially with the risk of them being readmitted or you discharge them to inappropriate or unacceptable settings that don’t actually enhance their quality of life.”

Meanwhile, National figures on planned discharges reveal a marked rise in people moving from ATUs to “other” settings; from 160 transfers in March 2016 to 465 in October 2018 – that’s 20% of all 2,350 people. NHS Digital, which collates the statistics, does not collect information on what “other” settings constitute or on locked rehab or discharges into private placement.

Chris Hatton, Lancaster University professor of public health and disability, says: “It’s hard to know where people are going, what these ‘other’ places actually are, and whether people being moved notice any difference from ATUs…without transparency, it’s possible to game the statistics to make the ‘transforming care’ numbers look good while consigning people to invisibility in places that feel very similar to inpatient units.”

The ultimate answer, says Gary Bourlet, co-founder of campaigning organisation Learning Disability England, is that people need decent jobs alongside good quality community housing “but there’s no national mandate for driving this forward.”

- Read the full story in today’s Guardian