By 2050, an estimated 940 million disabled people will be living in cities, lending an urgency to the UN’s declaration that poor accessibility “presents a major challenge”.

The Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and laws like the Americans with Disabilities Act, the UK’s Equality Act or Australia’s Disability Discrimination Act, aim to boost people’s rights and access. Yet the reality on the ground can be very different, as Guardian Cities readers recently reported when sharing their challenges in cities around the world.

Barriers for physically disabled people range from blocked wheelchair ramps to buildings without lifts. The cluttered metropolitan environment, meanwhile, can be a sensory minefield for learning disabled or autistic people.

Cities benefits from accessibility; one World Health Organisation study described how people are less likely to socialise or work without accessible transport. Cities also miss out on economic gains; in the UK the “purple pound” is worth £212bn , and the accessible tourism market for disabled visitors is worth £12bn.

My Guardian report today looks at some of the most innovative city-based developments in the UK, Europe, Asia, America and Australia. These include skyscrapers built using universal design principles to the retrofitting of rails, ramps and lifts in transport services or digital trailblazers that help disabled people navigate their city.

For example, mapping apps make navigating cities a doddle for most people – but their lack of detail on ramps and dropped kerbs mean they don’t always work well for people with a physical disability. The University of Washington’s Taskar Center for Accessible Technology has a solution: map-based app AccessMap, allowing pedestrians with limited mobility to plan accessible routes.

Wheelchair user John Morris, who runs advice site Wheelchair Travel, says: “Seattle’s geography, with changes in elevation, sidewalk and street grade on a block-by-block basis, often make it difficult to navigate in a wheelchair. AccessMap combines grade measurements with information on construction-related street closures and the condition of sidewalks to plot the most accessible course, pursuant to the user’s needs. I would like to see AccessMap included as part of a holistic accessible route planner that includes the city’s public transportation services in building the most effective journey. Pairing AccessMap with the city’s route planner tool or with transit directions from Google Maps would make getting around Seattle easier for people with disabilities.”

Steve Lewis, a 69-year-old manual wheelchair-user who has helped co-design the Seattle technology, adds: “I spend a lot of time in downtown Seattle and am well aware of what a barrier the hills are to wheelchair travel. I have learned from experience how to navigate the downtown corridor. The best routes for someone in a wheelchair will take advantage of elevators in buildings entering on one street and exiting several stories higher on the adjacent street. AccessMap is an effort to automate and make accessible the knowledge I have acquired through experience. It currently shows graphically the steepness of the terrain. The Taskar Centre is involved in a major effort to automatically display the best routes for wheelchair users with knowledge of elevators and mass transit including the hours they are available.”

Through its related OpenSidewalks project, the Taskar Centre is developing a system to crowdsource extra information like pavement width, or the location of handrails. Nick Bolten, AccessMap and OpenSidewalks project technical lead, says: “AccessMap tackles a neglected problem: how can you get around our pedestrian spaces, especially if you’re in a wheelchair? AccessMap lets users answer this question for themselves, and OpenSidewalks will help add the information they need.”

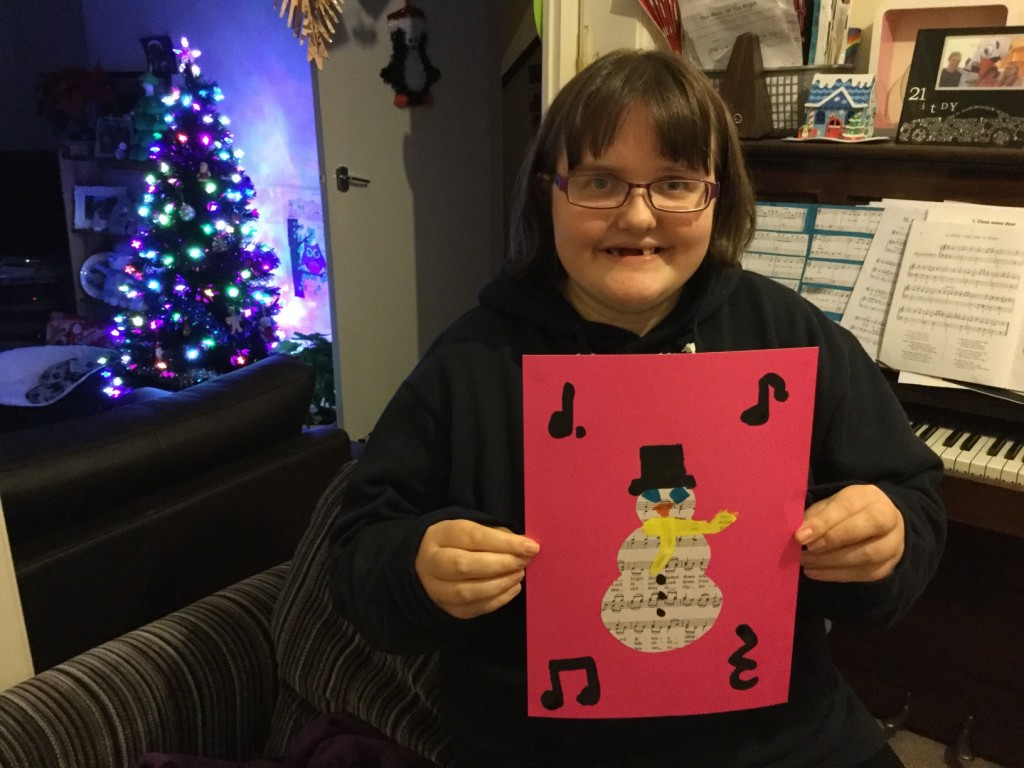

In another US-based project, this time in Sonoma, California, a $6.8m supported-housing project, Sweetwater Spectrum, is a pioneering example of autism-friendly design. Autistic people can be hypersensitive to sound, light and movement, and become overwhelmed by noisy, cluttered or crowded spaces. However, the scheme is designed according to autism-specific principles recommended by Arizona State University. The complex, which opened in 2013, includes four 4-bed homes for 16 young adults, a community centre, therapy pools and an urban farm – all designed by Leddy Maytum Stacy Architects.

Noise is minimum thanks to quiet heating and ventilation systems and thoughtful design – like locating the laundry room away from the bedrooms. Fittings and décor reduce sensory stimulation and clutter, with muted colours, neutral tones and recessed or natural light used rather than bright lighting. Marsha Maytum, a founding principal at Leddy Maytum Stacy, says the design “integrates autism-specific design, universal design and sustainable design strategies to create an environment of calm and clarity that connects to nature and welcomes people of all abilities”.

And there’s another great project from Leddy Maytum Stacy in nearby Berkeley, the Ed Roberts Campus, “a national and international model dedicated to disability rights and universal access”. The fully accessible building, named after the pioneering disability rights activist Ed Roberts, is home to seven disability charities, a conference, exhibition and fitness spaces, plus a creche and cafe. Features include a central ramp winding up to the second floor, wide corridors and hands–free sensors and timers to control lighting.

No city is wholly accessible and inclusive, but there are groundbreaking examples leading the way – and we just need more of them.

Read the full piece in the Guardian here.