Tomorrow is the seventh anniversary of an event that reflects an enduring national scandal. A long-running scandal that doesn’t trigger public or political outrage.

I’ve written an opinion piece for the Guardian about this today.

On May 31 2011 BBC’s Panorama exposed the abuse of people with learning disabilities at the NHS-funded Winterbourne View assessment and treatment unit (ATU) in Gloucestershire.

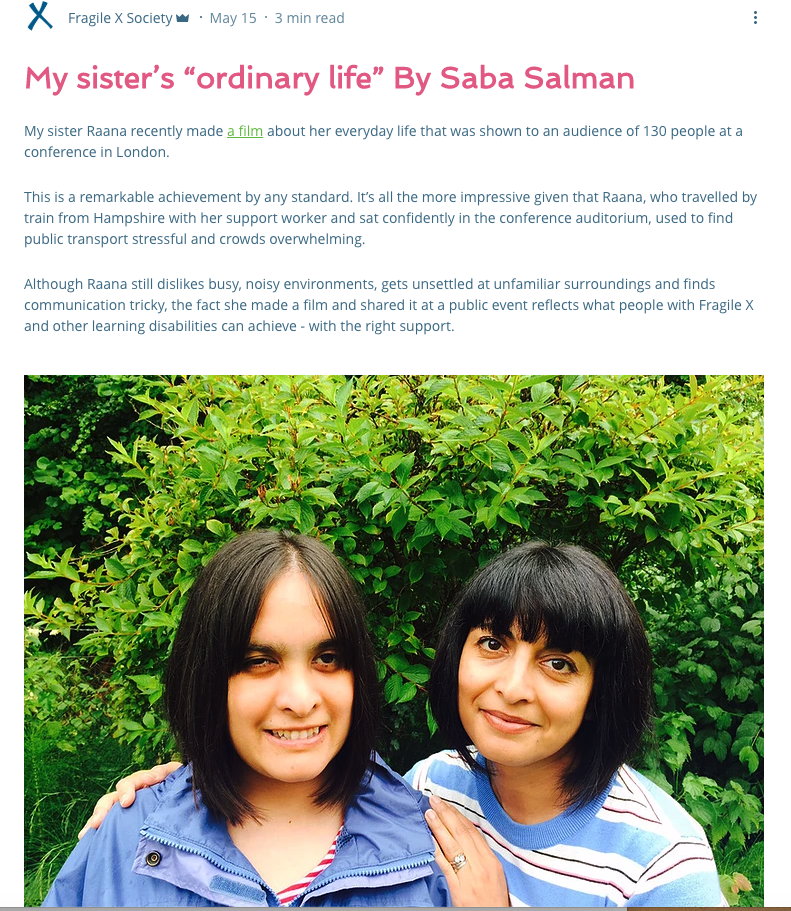

There are around 1.5m learning disabled people in the UK, including my sister, Raana. But the general disinterest in learning disability means that tomorrow’s anniversary will not trouble the national consciousness.

Rewind to 2011, and Winterbourne View seemed like a watershed moment. The promise that lessons would be learned was reflected in the government’s official report [pdf], and in its commitment to transfer the 3,500 people in similar institutions across England to community-based care by June 2014. Yet the deadline was missed, and the programme described by the then care minister Norman Lamb, as an “abject failure”.

Since then, various reports and programmes have aimed to prevent another Winterbourne View. These include NHS England’s “transforming care” agenda, which developed new care reviews aimed at reducing ATU admissions.

Yet despite welcome intentions, government figures [pdf] for the end of April 2018 reveal that 2,370 learning disabled or autistic people are still in such hospitals. While 130 people were discharged in April, 105 people were admitted.

This month, an NHS investigation reflected how poor care contributes to the deaths of learning disabled people. It found that 28% die before they reach 50, compared to 5% of the general population.

Unusually, this “world first” report commissioned by NHS England and carried out by Bristol University came without a launch, advance briefing or official comment. It was released on local election results day ahead of a bank holiday. Just before shadow social care minister Barbara Keeley asked in the Commons for a government statement about the report, health secretary Jeremy Hunt left the chamber.

The most recent report was partly a response to the preventable death of 18-year-old Connor Sparrowhawk at a Southern Health NHS Foundation Trust ATU. The Justice for LB (“Laughing Boy” was a nickname) campaign fought relentlessly for accountability, sparking an inquiry into how Southern Health failed to properly investigate the deaths of more than 1,000 patients with learning disabilities or mental health problems. The trust was eventually fined a record £2m following the deaths of Sparrowhawk and another patient, Teresa Colvin.

Recently, other families whose learning disabled relatives have died in state-funded care have launched campaigns, the families of Richard Handley, Danny Tozer and Oliver McGowan to name just three. Andy McCulloch, whose autistic daughter Colette McCulloch died in an NHS-funded private care home in 2016, has said of the Justice for Col campaign: “This is not just for Colette… we’ve come across so many other cases, so many people who’ve lost children, lost relatives”. Typically, the McCullochs are simultaneously fighting and grieving, and forced to crowdfund for legal representation (families do not get legal aid for inquests).

To understand the rinse and repeat cycle means looking further back than 2011’s Winterbourne View. Next year will be 50 years since the 1969 Ely Hospital scandal. In 1981, the documentary Silent Minority exposed the inhumane treatment of people at long-stay hospitals, prompting the then government to, “move many of the residents into group homes”. Sound familiar? These are just two historic examples.

If there is a tipping point, it is thanks to learning disabled campaigners, families, and a handful of supportive human rights lawyers, MPs and social care providers. Grassroots campaigns such as I Am Challenging Behaviour and Rightful Lives are among those shining a light on injustice. Care provider-led campaigns include Certitude’s Treat Me Right, Dimensions’ My GP and Me, Mencap’s Treat Me Well.

Pause for a moment to acknowledge our modern world’s ageing population and rising life expectancy. Now consider the parallel universe of learning disabled people. Here, people get poorer care. Consequently, some die earlier than they should. And their preventable deaths aren’t properly investigated.

You can read the full article here.