When newlywed Tessa got back to the hotel with husband Mark after their wedding, she found he’d arranged a surprise – he had scattered flowers and balloons around the room.

As Tessa recalls in a new project and book, Great Interactions by photographer Polly Braden: “I kept laughing at Mark – he was trying to throw the flowers around me…He’s happy now he’s married. We love each other. Being married doesn’t feel any different. That’s it. It makes me feel happy. Mark’s already got his name, so his wife will be Tessa Jane Ahrens, that’s mine and Mark’s choice. I used to be Warhurst – not anymore now. When my bus pass has run out they’re going to change my name on it.”

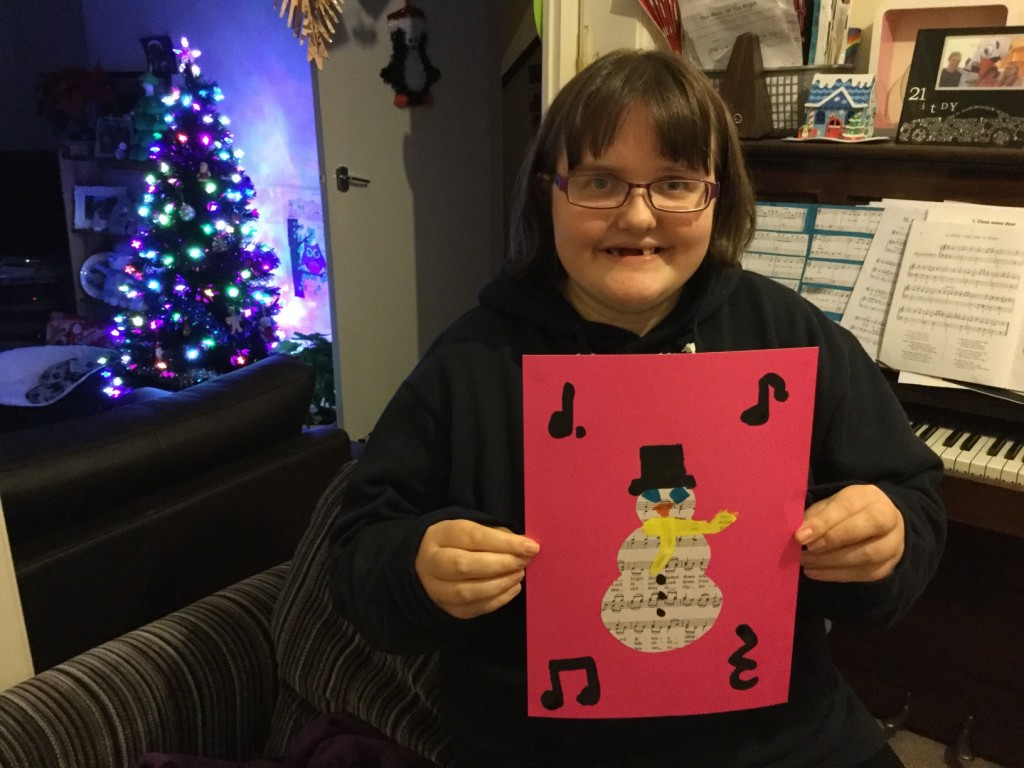

The couple’s story is one of many documented in Braden’s book and exhibition. The project aims to capture the daily lives of people with learning disabilities, from everyday interactions to landmark events like Mark and Tessa’s wedding. The book will be published next month and the images will also be featured in an exhibition at the National Media Museum, Bradford.

Polly Braden spent two years working with social care charity MacIntyre and the people it supports across the UK. The resulting work, refreshingly, offers a glimpse of the diverse, individual, ordinary lives of people with learning disabilities – around 1.5m people in the UK have a learning disability, but the population, usually seen as a homogeneous mass or single statistic, is defined by needs and lack of ability, as opposed to current or future potential.

Braden’s project also comes at a time when public sector funding cuts threaten vital support services and, as I’ve written before, families fear that the long-promised improvements to the care of people with learning disabilities may never happen.

Braden’s work does not gloss over the problems, but offers a different perspective. She explains: “The people I have met all have stories about the barriers, prejudice and ignorance they and their loved ones have faced in simply trying to have fair opportunities in life. But their stories are also inspiring and filled with heart-warming moments which would have seemed impossible to imagine earlier in their lives – from being active and using public transport to graduating from high school and getting married.”

The photographer’s aim was to try to take photos about support “at the best it can be, but not to gloss over the profound problems in the provision of care and support and the challenges around this as well”. The project tries to look at what can be achieved for people when they are given good support, “and to talk about what happens when they are not”.

The aim of the project is “to challenge out-dated, institutionalised images and improve public awareness by recognising and highlighting the every day interactions and life changing experience of people with a learning disability”. It also focuses on social care professionals’ attitudes towards and relationship with the people they support. As one support worker, Raul, told Braden of the person he works with: “Mikey needs this kind of support: he needs to be around people who know and understand him, who are willing to go a step further and discover the bright and amazing person he is.”

* All photographs by Polly Braden, the book Great Interactions is out in March and the six-week exhibition at the National Media Museum, Bradford, opens on 27 February.

* To mark the book’s launch, the National Media Museum and MacIntyre are asking people to share photos of “everyday moments that make life matter” on Instagram, using the hashtag #IamMe – see the website for more information

* For more reading, see this Guardian feature published at the weekend..

This blog was amended on Monday 29 February to include the Great Interactions Live website